The Luminous Vertigo of Crisis

The "Continuity Thesis", the End of Marxism and my trip to Washington DC

I’ve spent the most of the last week in Washington DC, a short trip that somehow felt infinite in length. The last time I was there was probably 2010 or 2011, a completely different time—it was he high watermark of the post-political era, as the slow churning aftermath of the recession had been paper-overed by the technocratic enthusiasm of the Obama administration. Cracks in that order were just starting to form, but it was winter and the city was covered in snow. It all seems very hazy and dreamlike now.

I had arrived this time expecting a fevered and nervous energy pulsing through the synaptic cables of the imperial center, some kind of a jangling induced by the impending return of Donald Trump, by the chaos burning in the peripheries, and with the specter of generalized stasis in the state’s administrative functions. Last month James Pogue wrote an article for Vanity Fair about the fractioning nature of the foreign policy establishment—besides the dollar, this is the only thing in Washington being administered. The capital city, Pogue wrote, was gripped in a kind of mad heat, an intractable paranoia gripping the bureaucratic class.

But to me DC felt subdued, quiet under a blanket of late autumn dampness. A certain catatonia had set in, and I was told that even the price of Uber rides had fallen. Maybe that’s the indicators, registered in noise levels and the fluctuating prices of ephemeral commodities, of the psychic fallout of what Anton Jäger has described as “hyperpolitics”. For Jäger, this is the re-introduction of the political into everyday life in its most fevered form, pulsing and swarming and always shifting, operating not only at the level of administration and deliberation but seeping down into the give and take of interpersonal relationships.

In the age of hyperpolitics, nothing is ever achieved: it is ‘politics without political consequences’. A curious paradox forms, since out there at the top of the political order, soon to be headed again by Trump, not much is going to change, the inertia is only going to continue. At the same time, because the political has been personalized—it has become the default form of collective experience in an epoch defined by unending atomization—the hand-off back to the GOP comes as a mortal shock to the mind (though I wonder how much of that shock is more feigned, played out as an expected ritual, rather than something real and concrete).

Real or not, the city felt tired.

I was meeting my friend Tom in DC. I know him through Twitter/X, and this would be the second time we’ve met in person. The first time was last year in New Orleans, where we hung out at the Napoleon House a lot and I subjected him to parts of my self-designed JFK assassination walking tour. That ‘tour’ covered spots like Oswald’s grade school and several houses owned by CIA asset/conspirator Clay Shaw. One of those houses sat in proximity of a voodoo museum that functions as a shrine; it made me think of the story, possibly apocryphal, that Papa Doc, the CIA-backed dictator in Haiti, had stabbed a voodoo doll of JFK some twenty two times. I left two dollar bills and three cigarettes on one of Loa’s altars.

Late Friday night we went to many different places, including the neighborhood known as Navy Yard. Once an industrial area with a largely working class population, Navy Yard has now been completely redeveloped into an entertainment district peppered with the sorts of restaurants and bars that you can generally find in any other major urban area; blocks and blocks are wrapped by countless buildings of that now-ubiquitous style, 5-over-1, that seem to stretch off into far horizon. Standing on a rooftop bar and looking out on it makes the total complex appear as the Grand Canyon, towering residential dwellings churned up from the earth like jutting rocks and cliffs. It’s where the countless lobbyists and consultants that run the empire’s day-to-day operations go to sleep at night.

The supermoon swung overhead, its radiant light shrouded partially by low clouds. During a supermoon, our lunar neighbor sits at perigee, which means that it is the closest to earth in its elliptical orbit. A perigee shouldn’t be confused with an object’s perihelion: in orbital mechanics, that latter term is reserved for stellar bodies moving in a solar orbit, while the former is used for things that are arcing in slow and invisible rings around our own planet.

Anyways, a picture of me and Tom at the rooftop bar:

The next four days or so were suffused with a manic and near-sleepless energy quite unlike the DC I had initially encountered, and we had many conversations about thoughts that have been banging around in my head for a few years but never really have been organized in a way that I felt comfortable with. A lot of this might be familiar to readers of this blog or followers on Twitter/X (RIP), but I’ll try to stack it together in a way that hopefully makes sense:

Theses

Proposition A: Actually-Existing Socialism auto-generates a fundamentally new class contradiction internal to itself.

An idea, unfashionable for a long time but becoming more generally acceptable in left-wing discourse: the Soviet Union and People’s Republic of China constitute the real, concrete reality of socialism as having a historical existence. Neither, including the latter in its current form, constitute anything like a “degenerated workers state”, a “bureaucratic collectivist state”, or “state capitalism”.

The passage to socialism has an objectively historical character, operating at a degree far beyond the subjective whims of particular actors or groups of actors. The key insight of Marx is that the concrete existence of capitalism makes the reality of socialism possible—it serves as its foundation and is encoded with an auto-abolition that makes possible a future beyond capitalism. The existence of the Soviet Union and the PRC serve to disclose this reality in ways analysis and theory never could.

Class struggle persists within socialism, one directed not only against the bourgeois class—which persists—but against a new class that, while germinal within capitalism, fully realizes itself in the conditions of socialism.

Socialism develops the productive forces far beyond the checks and road blocks that capital throws up against this development. Productive developments calls into being a panoply of specialists, managers, experts, regulators, technicians and coordinators—these are the empirical manifestations of the new class, which takes as its primary object the task of planning and the creation of solutions.

As it consolidates itself within the irrevocably fixed trendlines of development, the new class begins to achieve higher degrees of self-consciousness. This consciousness leads the class to assert itself not only within the matrices of production, but at a political level. It moves itself against the bourgeoisie and the proletariat alike.

Proposition B: The conflict between two class forces shapes the total content of Actually-Existing Socialism.

The whole of the story of Actually-Existing Socialism, the changes and contingent events that took place between them, express the dynamics of this new class struggle between the proletarian and the new class.

In the Soviet Union in the time of Stalin, it was the increasingly-consolidated new class that was repressed through the purges and accompanying events. Insofar as the ‘old Bolsheviks’ were themselves targeted, it was the ones who tended to act as the intellectuals who sought to shape the architecture of proletarian civilization according to the perspective of the new class.

Stalin’s gambit was to blunt the power of the new class and re-instill a proletarian political power base within the Soviet bureaucracy itself. This can be glimpsed empirically by the rise of those of a proletarian background within the bureaucracy.

Contrary to many theorists of the new class that exist on the political right, the ‘bureaucrat’ and the new class individual are not synonymous terms. Bureaucracy has its own rationality that must be grappled with, and that rationality easily complements the universalizing gaze of the new class. But at the same time, bureaucracy can be wrestled back by other class forces and put to work for different uses. Bureaucracy has a historical character and is bound to class society, but it is not a one dimensional construction: it is a terrain onto which the struggle spills itself.

Under Khrushchev, the forward momentum against the new class was halted and reversed. The scientist, the engineer, and the planner became the dominant forces in Soviet society, and with them, cultural forms grounded in cybernetics, utopian dreams of space, and abstract intellectualism proliferated. The rising class of managers and experts would soon group themselves at the top of state-owned industries; when now-inevitable collapse of the Soviet Union would arrive, many of these individuals became the first true ‘capitalists’ in the post-Soviet sphere: history running the new class backwards, transforming them into oligarchs.

Proposition C: The Sino-Soviet split signals the transposition of this class conflict to the level of geopolitics.

Mao grasped the struggle of the new class in two modes: against the power of this class within the bureaucracy, and within the organization of production itself. In the case of the latter, he looked to ‘light industry’ as a counterbalance to a lopsided emphasis on ‘heavy industry’—one of the chief problems in the Soviet experiment. Light industry means speed, decentralization, and a greater increase of proletarian autonomy when it comes to production.

The introduction of light industry at the level of production finds its complement at the level of international relations in the Sino-Soviet split. The context of the Sino-Soviet split was the Khrushchev counter-revolution, which is to say, the victory of the new class within the Soviet experiment. This means that the Sino-Soviet split itself was a reflection of the struggle between the proletarian and the new class: it had now ascended to the domain of geopolitics.

The Sino-Soviet split marks the beginning of what eventually became known as “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics”. What do “Chinese characteristics” mean in this context? It illustrates the effort of the proletariat and peasantry to achieve self-realization within the specificities and particulars of their time and space, within their historical ground. We drop from the towering heights of geopolitical command and strategy to the shade of existential experience: an uncovering of meaning, which is something totally contrary to the logic of the new class. It can only stand as the liquidator of Spirit.

The Sino-Soviet split also discloses what would eventually become described, in geopolitics, as ‘multipolarity’. From the perspective of its adherents today, multipolarity illustrates the immanent crisis of the ‘unipolar’ world—the singular empire dominated by the United States, as different blocs secede from this machine and revolt against it. Yet this was disclosed already in the Sino-Soviet split: the Cold War could not be understood as a conflict between two poles—the Americans and the Soviets—but the interrelated and antagonistic triangle of the United States, the Soviet Union, and China.

I don’t have a 5th point for here, but for the same of symmetry I’m writing this as a stand-in for a 5th point-to-come.

Proposition D: The Cultural Revolution as an event marks the intensification of this class struggle within Chinese socialist civilization.

The Cultural Revolution operated one two different, but intricately interwoven planes. The first was the drive to realize the new world of socialism in a cultural mode, the impossible striving for a Year Zero, which can be approached but never achieved. The most violent and regrettable points of the Cultural Revolution arise from the breakdown of this possibility.

The second aspect is that the Cultural Revolution continues the struggle against the new class in a more intense, all-encompassing frame: the whole of society swept along as this struggle it pushed to its absolute limits, threatening to bring down the world itself in its frantic momentum.

The Cultural Revolution was immediately presaged by the “bombard the headquarters” campaign launched by Mao. This was the point in which Mao, at the head of the Party, urged the population to revolt against that same Party. At the most general and immediate position, “bombard the headquarters” was taking aim at an increasingly sclerotic Party bureaucracy that was detaching itself from the proletarian and peasant base. In a more specific register, it targeted elements of the Party that remained closely aligned to the Soviet mode. It constituted an internal purgation of what had happened within the geopolitical sphere with the Sino-Soviet split.

The Cultural Revolution had a populist character, which is something it shared with all prior experiments in Chinese socialism. Populism is a form of politics that is directly antagonistic to the new class: it is grounded in the lived experience of the people themselves, as an attempt to bind individual experiences into a collective unity. Unlike the west, where populism is constantly pulled back into the support pillars for the dominant order, the populism here acts as a bridging point to proletarian consciousness—the collective unity that is striven for by the populist as a class existence.

5th point-to-come (maybe).

Proposition E: There is a fundamental continuity between Mao and Deng, between the Cultural Revolution and the Reform and Opening-Up.

One element of the Reform and Opening-Up period, the turn towards marketization and ‘globalization’ by China, is that it simply marks a continuation of Mao’s emphasis, formed as far back as 1956, that the country needed to develop light industry to counterbalance heavy industry and all that it entails. Light industrial processes became the basis for the sort of market behavior that was unleashed in the Deng years, as intensification of industrial zones pushed China towards its export strategy. This is one case of continuity between Mao and Deng.

Another element is the development problems posed by the Sino-Soviet split. As a developing country, China required technology and it required capital. In breaking with the Soviets, China needed to look elsewhere—and thus the strange pact with the Americans, Mao meeting Nixon, was born. What’s not often known is that Mao’s diplomatic overtures began during the administration of Lyndon Johnson, and that an economic relationship was always on the table. A desperate strategy rife with dangers: the other seeds of Deng can be found here.

It could be said that the Reform and Opening-Up could never have happened without the Cultural Revolution. Without the generalized sense of chaos, forces within the Party bureaucracy could have easily blocked the progression, and the power base that would have been most equipped to mobilize in support of those forces—the students—had been scattered to the far corners of China’s countryside.

In the continuity between the Cultural Revolution and Reform, the great explosions of social energy swirling like a maelstrom within Chinese society were seized and converted into fuel for a development machine; it flowed outwards across the world in the form of production circuits and monetary exchange. From communes to commerce: what appears like tragedy as something forced by the iron grip of necessity. The material premises of reality cannot be found in an excavation or even creation of culture alone.

The Reform period could have easily called the new class back into power in China, and many way it has—it unleashed the era of the “Red Engineers”, and the technocratic elements in the Party remain alive. At the same time, it is clear that Deng took steps to try and ward off this transition in advance, through his efforts to blunt the power of industrial groups that harbored, still, a belief in the old Soviet mode of development capable of being realized in new form for the new age. This process isn’t complete, it continues until this day and perhaps will indefinitely, as historical negotiation, shuttering movements and sidesteps, but going forward nonetheless, advancing into profound territories yet to even be imagined.

Codicil

In the movement from the Soviet experience to that of China, Marxism pulls itself towards its final hour. This isn’t to say that Marxism has been disproven, or that it has exhausted itself, but that it, as a doubling of analysis and practice, stands at the precipice of its true self-realization. A completion of a process is also a process’ self-overturning, the moment when it lives more full and alive than it ever has before while also signaling the moment of its own death.

Marxism lives and breathes the crisis of capitalism, works to unveil the fact that crisis is intrinsic to these arrangements of production and social mediation, and that crisis is baked into its very foundation at the point of inception. Crisis is movement, transition, reverberating shakes of the conversion of things into their opposite as it echoes loudly in the world. It is the motor and the ladder.

Neither crisis nor capitalism (nor the existence of the bourgeoisie and proletariat) have made their exit from the world stage, but what has changed is the fundamental underlying logic that governs historical development in our time. What does it mean for Marxism to say that the law of value no longer operates autonomously, but is instead an appendage of state action? What does it mean to say that capitalism is now little more than a zombie, neither alive nor fully dead?

Mao’s inversion of the dialectic, the division of the One into Two—which finds its immediate predecessor with Lenin’s own statement: “the splitting into two of a single whole”—demarcates the point of Marxism’s self-abolition at the level of philosophy. Contra the critiques lobbed by French theory, Mao wasn’t simply flipping the dialectic upside down while retaining haphazard binary structures; it instead stands as a cipher that reflects a fundamental fracturing that takes place internal to the One, perhaps even precedes the One—real multiplicity, a One that is open to the forces of chaos.

At the level of the Chinese experiment in socialism itself, the division of the One into Two is instantiated materially as the generation of productive contradictions. Look at the transformations: the wild internal social differences that were already present in the immediate post-revolutionary period find their re-expression in the great fluctuating movement of the civilization-state’s internal populations, their drifting pull towards the Pearl River Delta where economic planning collided with the intensification of the cash nexus. Proliferation of special economic zones, negative spaces opened up by the Party, acceleration of commerce, technological development and investment flows in the name of progressing socialism forward.

The liquid-hot momentum of the revolutionary masses undergoes a radical conversion, and the pure potential of the higher stage of development ushers in a lower form to draw itself into existence (two modes of production can exist co-exist, bringing the full contradictions of each to bear upon one another).

This spiraling succession of productive contradictions reaches an apotheosis in Xi, who redeploys it outwards across the whole of the globe by speaking of the emergence of multipolarity and worldwide economic integration as two fundamental and irrevocable trendlines that are fixed at the level of history: our future. Multipolarity and marketization appear as absolutely antithetical terms. Multipolarity, the existence of which is disclosed in the Sino-Soviet split, as the self-grounding of a people in their particularity, and the disintegrative force of the world market, operating at the level of the universal—what will fall out from the seismic shock of their mutual confrontation (-without reconciliation)?

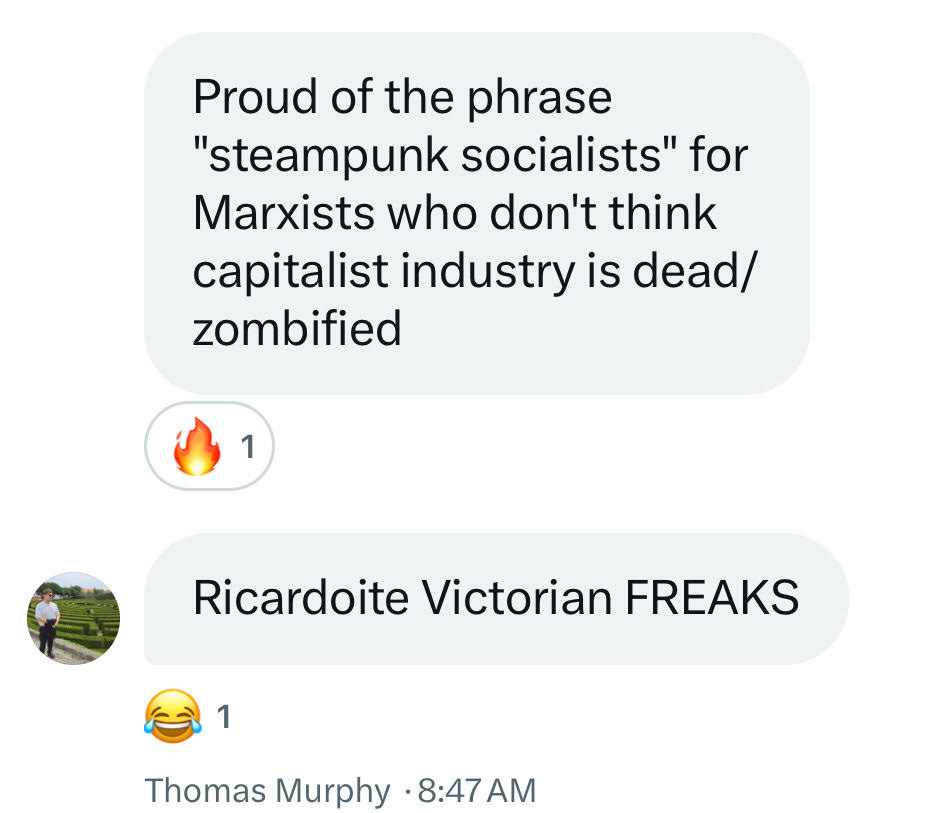

In the West, particularly in the stagnant imperial core of the United States (because Europe is merely a vassal zone), this question becomes paramount. There is a strange riddle of fate that has befallen us: it is clear that lines are being drawn, even here, between a waning bourgeoisie and an emergent new class strata—a tripartite class formation becoming the dominant form of American sociality. This iteration of the new class, which only faintly resembles its counterparts in Actually-Existing Socialism, operates, in the words of a friend, “as if blind market forces still dominate, so they do very little with the immense transformative power they wield”.

This situation persists even though they know better, they sit at the levers of the Metacartel, the impending Thing which produces the conditions that make possible the persistence of capital(ism) after its own auto-termination. The western new class moves backwards, eyes turned away, from its own historical position, even as it begins to assert itself as a potent political force.

But the very existence of a new class in the West unveils a secret. If this is the fundamental class contradiction of socialism, then we too are effectively a socialist society, or at least exist in a highly advanced mode of production that has become socialized, even if this mode exists in a stagnant and retrograde state. Socialism realizing itself not as a future shot through with the immediacy of meaning, but as the permanent management of catastrophe.

Several options present themselves at these fixed crossroads. There is a certain temptation to indulge in the infinite recline of geo-historical sadness, to quietly meditate upon the damaged contours of a fallen world. At best this path could present positive developments in aesthetic registers, but at worst—and the more likely outcome—is the distilling of this meditation into the most reactionary of political projects.

The other path means being a Marxist after the end of Marxism, which for us in the west means something quite different from the existence of a hegemonic Marxist-Leninist party drawing socialism into relief. It means advancing on uncertain terrain, a landscape stripped of guarantees, and moving in a world that has swung out of balance with itself.

This is also a question of theory and philosophy. The Copernican Revolution that Marx carried out not only unveiled the inner logic of capital while it still was alive: the revolution also closed the epoch of philosophy itself. ‘Theory’, as a mode of reflection, analysis, and critique, is what arose in the shadowy aftertracings of philosophy’s passing; it is, simply put, all criticality that is downstream from the Marxist project (even at those points when theory could only lurch into increasingly banal self-reference and the repetition of concepts stripped of their historical particularity).

We continue to make theory, but little of it contains the shock of the new, it hardly draws the square and circle of the future into the present. Perhaps this signals, in some strange way, the re-opening of the philosophical project itself, but in a particular mode and way of being. “The only philosophy which can be practiced in face of despair is the attempt to contemplate all things as they would present themselves from the standpoint of redemption”.

Departure

Final night in DC: I wandered around the city, moving from Meridian Hill Park down towards the Washington Monument, which stands 555 feet tall. That the obelisk, a form in itself that is inundated with symbolic function, sits at this height is, so they say, total coincidence. Half way there I changed my mind, turned back, and slowly meandering back towards Tom’s neighborhood. The plan was to meet Tom and Jake, another friend, at Duffy’s, a little Irish-themed sports bar in the DuPont Circle neighborhood.

I arrived early, bought a beer, and sat down at a table outside to watch the people passing up and down the sidewalk. I wasn’t there but for a minute when a man came up and asked if he could sit with me. His name was Marcus, and he was a character in the literal sense of the word: theatrical in personality, with an avalanche of words and frantic observations and little stories that came tumbling from his mouth at every second. He had just moved to DC from Houston, Texas, a city I know very well. This excited him.

Across the street from Duffy’s is a high rise apartment building, each little unit glowing with light in the DC night. Look, Marcus said, pointing up. A woman in an apartment, five or six stories up, was drawing the apartment blinds closed, muting out the soft glow from the interior. I love to see that, he said. I love to watch people closing up for the night. It’s like being at the end of a play, when the curtains come down.

I told him that I thought this was a little voyeuristic and he winked. It’s very voyeuristic.

Marcus declares himself to be a highly spiritual person. Just an hour prior he had asked God what he should do next, which way to turn—just give me some sort of sign. As he kept his eyes on the apartment building, monitoring the activities unfolding in each room, he lit a cigarette. Marcus had taken no more than three puffs when another stranger walked up to us. This man wore a tattered baseball hat and carried a small brown backpack. The fingers on his right hand were twisted and bent from some ancient injury. He looked directly at Marcus and told him: you should quit smoking. You’re a man of God, so quit smoking. The man turned to me, extended the hand with the twisted fingers to shake mine. Tell your friend he needs to quit.

The man ambled away, slowly moving up P Street in the direction of DuPont Circle. Marcus acted stunned. Do you think that was God? he asked me and, with a nervous confidence that momentarily broke his theatrical persona, as a person sagging under the weight of revelation’s burdens, answered his own question. It was. It was. It was. That was God.

Rare to be found analysis of what happened in China. Now It's time to do my dumping!

"Fanatical orthodoxy is sometimes the first step toward more radical self-expression. Islamic fundamentalists may be extremely reactionary, but by getting used to taking events in their own hands they complicate any return to “order” and may even, if disillusioned, become genuinely radical — as happened with some of the similarly fanatical Red Guards during the Chinese “Cultural Revolution,” when what was originally a mere ploy by Mao to lever out some of his bureaucratic rivals eventually led to uncontrolled insurgency by millions of young people who took his antibureaucratic rhetoric seriously."

This event is detailed thoroughly in this analysis done by the S.I. at the time:

https://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/11.China.htm

"Soon, however, the workers, exasperated by the excesses of the Red Guards, began to intervene on their own. When the Maoists spoke of “extending the Cultural Revolution” to the factories and then to the countryside, they gave themselves the air of having decided on a movement which had in fact come about in spite of their plans and which throughout autumn 1966 was totally out of their control."

Shanzhai!

You were right but a bit neutral when you talked about the "opening up" of China by Deng. When this happened it was basically when Joe Margarac in the States' lost his vril, the working class of the West became redundant.. during the 'computer revolution' or counter-revolution, shall I add, when blue collar jobs diminished, more automation, the weakening of the unions struggles, and thus its consciousness, the increasing atomization and retreat to consumerism, and then the mass of surplus chinese became the slaves in factories they are known for.

But in the last years they did "develop", they did "improve" their situations, materially, although with the cost of some state surveillance, and some primitive accumulation with chinese characteristics. Xi has and had a populist appeal. That's why he came to power, he was needed to 'calm down' the situation that was already chaotic at the time..

And yes, they fully applied cybernetics to their policies, that was what partly influenced the one-child policy (which, honestly, wasn't that bad, it's straining them now --economically-- but the Earth thanks alot). And is still very influential, more than ever with their mania for surveillance and everything virtual (WeChat, Weibo etc). It was some Qian Xuesens and Song Jians... rocket/missile scientists technocrats invited to meddle with politics.

Have you also seen the conversations between Kissinger and Mao? Here: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v18/d12

This site is also good, unique perspective from the not so known chinese left

https://chuangcn.org/blog/

Does it have some CIA backing? I wonder, hehe.

Other places to find good analysis related with China and elsewhere or something else are the sites of (now deceased, RIP) Loren Goldner and World Systems Theory Journal (WSTJ).

You should write a novel Ed. Great Eye and Voice

Where is the quote about philosophy in the face of despair from?