Is it capitalism that is collapsing?

A hastily written post on my phone…

…so apologies for typos. iPhones are less than ideal platforms for writing blog posts, but sometimes you gotta make due with what is on hand.

Jehu wrote a post yesterday that attempts to reconcile, among other things, Grossman’s version of Marx’s crisis theory, Keynes’ demand-driven economy theory and its deployment as crisis management, and Postone’s articulation of the notion of ‘superfluous labor time’. It’s good stuff:

The collapse of the gold standard in 1934 and again in 1971 takes center stage, serving as pivotal moments that allowed capitalism to reinvent itself and stave off crisis.

Picture the economy of the 1930s, reeling from the Great Depression. the model shows how the abandonment of the gold standard in 1934 unleashed a wave of inflation that, counterintuitively, helped restore profitability. By suppressing real wages, this inflationary period raised the rate of surplus value to a staggering 169%. It was like giving a shot of adrenaline to a failing heart, temporarily reviving the system but at a cost to workers.

As we follow the narrative through the post-war boom and into the turbulent 1970s, the model reveals another crucial adaptation: the growth of state intervention. Like a sponge absorbing excess water, the government expanded to soak up surplus labor, growing to nearly 10% of total economic output by 1980. This Keynesian approach to crisis management helped stabilize the economy, but it came with its own set of contradictions.

From here Jehu argues that because of increases in productivity, the amount of socially necessary labor time—the crystalline core of value that, through its luminous rays, expresses itself at level of appearance as price—decreases. Yet at the same time, labor time itself has failed to follow this curve and collapse along the way. This is because labor time has become superfluous, continued to balloon, both the duration and intensity of labor expanding and deepening. All the while real wages are suppressed, the amounts of real value imparted in the production of commodities declined, and capital effectively squeezes the working class like a wet dishrag, keeping itself afloat as the living conditions and ability of the exploited classes to reproduce their existence decay.

Jehu writes that the expansion of superfluous labor is directly tied to increasing levels of state intervention, and that “simplistic notions of capitalism's inevitable downfall” are challenged. The system instead proves itself to be “capable of remarkable flexibility and resilience”. The base is self-forming and ever-shifting; it modulates itself as crisis crashes against it. I’m in total agreement with Jehu on all these fronts, from top to bottom.

My one quibble is over a conceptual understanding of ‘capitalism’ and its ability to transform and mutate, forever pushing the terminal crisis into the distant historical horizon.

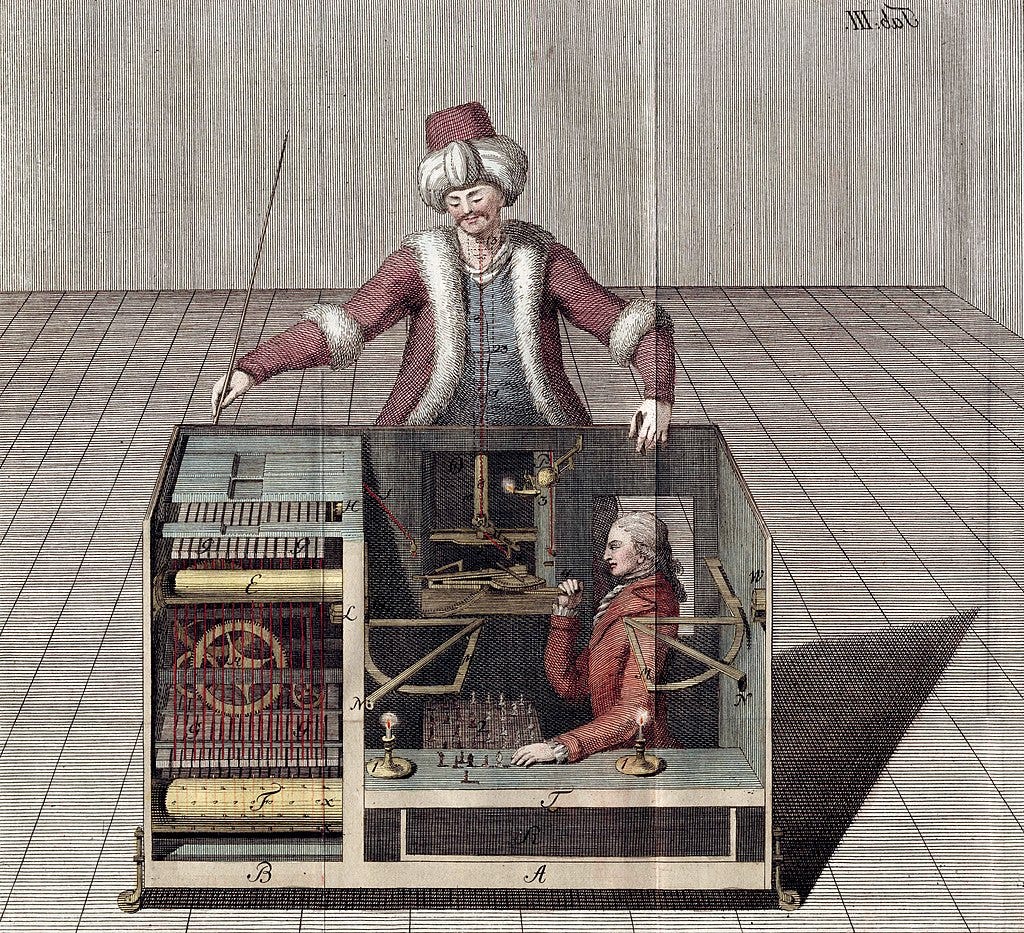

Look at some of the methods that Marx uses to describe capital: it is a “self-moving substance”. The implications of the terminology is no accident of poetic flourish—this is his debt to German Idealism on full display. In Hegel, for something to engage in purposeful activity, to be able to carry out self-movement, is the hallmark of the Subject. Indeed, Marx’s critique of political economy contains within itself, repeatedly, the concept of capital as automatic, as a Subject in its own right. Automaticity, to be an automaton—this does not mean to be moved by exogenous pulleys, ropes, levels, and the actions of external agent. A Subject moves of its own endogenous force; its action is circular, returning and self-returning. It pushes itself into the world, and through its actions it negates the conditions would otherwise totally condition it.

Jehu—rightfully—points out that capitalism persists through state intervention. But here we have a problem. If capital(ism) requires the state in order to perpetuate itself, then capital is no longer self-moving. If its operations require an external force to act as a motive cause, then it no longer exhibits the Subject position that Marx and classical political economy bestowed upon it.

One solution to this conundrum is to suggest that capital has thoroughly subsumed the state, with the implication that the state itself is just another node in the circular movement of capital’s own reproduction. That’s sort of the pop understanding of so-called ‘neoliberalism’ (dreadful term), which holds that the state, once some radical externality to capital, has been thoroughly penetrated and the areas once immune to commoditization have been pried open. This basis of this understanding of neoliberalism is rooted not in Marx, but Polanyi—this is how we get around to the idea that the state is ‘being shrunk’, made tiny, that its capacity for the “self-protection of society” (this is Polanyi’s organic response to the encroachment of marketization into everyday life) has been dismantled for profit.

The problem with these accounts are multifold. The first is that it veers into an ahistorical position: why does this happen to the state? Because economic actors are greedy, of course. Because of corruption, because of this or that. Jehu himself has thoroughly dismantled this position by showing, on the one hand, the deep structural relationship between state expansion and capitalist crisis, and two, the expansion of the state itself in the context of ‘neoliberalism’.

We also run into the problem of state autonomy, the question to what degree is the state autonomous from economic movements and the rule of the bourgeois class. I don’t feel like going down the state autonomy rabbit hole and I also don’t have time so it suffices to say that if the state can step in and manage the economy as it escalates through a compressive series of intensifying crises, then the state clearly has at least a ‘partial’ autonomy. Anything else would be a strict determinism and a close study of the historical record when it comes to the management of economic crisis shows the high degree of contigency—albeit a conditioned contigency—when it comes to the day-to-day movement of politicians and technocrats .

The other solution is the one that I’ve tried to tease out in my writings on the Metacartel: it’s not so much that the state is subsumed into the circuit of capital, but quite the opposite in some kind of arcane dialectical reversal—capital breathes and moves through continuous, and ever-expanding, state management. The state here is taken as an externality to capital, and it is bestowed a higher degree of autonomy that the previous solution would allot for. Maybe we can say that as capitalist crisis broadens, widens, shakes the system to its very, molten core, the state’s ability to act as a Subject unto itself also expands, learning to self-move in its own way. I dunno. That seems like a pat, just-so story.

This approach is grounded in precisely what Jehu’s argument notes that it does not account for, which is the financialization of the global economy from the 1970s onward. Chase the historical threads of financialization and, through the snaking passageways and closed doors, one will always arrive at the steps of the state itself, be it the Federal Reserve, the Treasury, or whichever agency or organization you prefer. Realpolitik and geopolitical imperative play a role just as important the calculus of actors competing or colluding on the market. Does ‘the market’ even exist anymore in any meaningful sense? Doubtful.

This, of course, presents another problem. If we take that state management is driving the economy, and deny by extension that capital is acting as the “self-moving substance”, that is, as a Subject, then is this capitalism as classically understood?

In the most immediate experience of reality the answer is yes: the rules of the game, when it comes to everyday experience of social and economic life, remain basically unchanged. At the highest, most abstract level, the level of the totality, the answer must be no. I think it’s fair to say (and this is just a microwave reheat of what has already been said on this blog) that this is some kind of inverted socialism, a socialism born from the FINAL crisis of capital, which has already happened, and the simultaneous defeat of the popular classes. We live in history’s coma.

Jehu says the following:

If past crises were deferred through monetary regime shifts and state intervention, what new adaptations might emerge to address the challenges of the 21st century? How long can the contradictions identified by the model continue to accumulate before reaching a breaking point?

This is something I turn over a lot in my head. Metacartel Theory is a theory of how there exists a structural force in the world that works to suspend crisis, but given that crisis is the basis for expanded reproduction, the annihilation of malinvestment, and the liquidation of superfluous capital, the fatal trade-off is one of unending stagnation. I agree with Jehu that by momentarily suspending crisis, it is deferred to a future point in time and that when it comes it will be much, much worse, wider and deeper than it otherwise would have been.

This crisis-to-come will not be a classical capitalist crisis. In fact, a conventional capitalist crisis itself could be a way to get more juice from the system (with that in mind, picture Trump 2.0 as the resurgence of the capitalist class in its more conventional mode, as signaled by the practical hand-over of the U.S. government to Silicon Valley. When the administration threatens the Fed’s autonomy—which is it doing, meekly but surely—this is the bourgeoisie directly challening the mechanisms that are keeping their system afloat).

The crisis-to-come won’t even be a crisis, because we are already in the regime of crisis, the Omnicrisis.. It will instead be catastrophic. Terminal phase-out. Geopolitical convulsion. Imperial death-spasm. The slow motion plummet—ontological destablization—we can already see its spectral outlines—any system that approaches the point of total closure approaches its own demise—

"Jehu—rightfully—points out that capitalism persists through state intervention. But here we have a problem. If capital(ism) requires the state in order to perpetuate itself, then capital is no longer self-moving. If its operations require an external force to act as a motive cause, then it no longer exhibits the Subject position that Marx and classical political economy bestowed upon it."

Point taken. This is an incorrect formulation of the problem. I should have begun as Engels did that "the modern State, again, is only the organization that bourgeois society takes on in order to support the external conditions of the capitalist mode of production..." Later, it renders this same bourgeoisie superfluous. But, despite this, capital remains the subject of history, not the state. I have been lazy in this regard and deserve the spanking you delivered.

Very nice concise statement of your thesis. Been thinking too about the fact that Vance et al seem to be challenging their own conditions, his whole talk of "cheap labour as a drug" comes to mind. Will the system really survive the withdrawal effects?