Frantz posed the following question to my ‘Dark Circuits: Oil Money and Covert Activities’ post:

I’m wondering where I could read more about the CIA and State Department’s preemptive efforts in North Yemen. Do you remember where you read that they were afraid of Soviet expansion into North Yemen and Saudi Arabia?

Since this is a very complicated and immediately relevant comment (given the high position of Yemen today in the grand geopolitical chessboard), I figured it’s worth of a bit of an elucidation. The short answer, for Frantz, is that some details can be found in Asher Orkaby’s book Beyond the Arab Cold War: The International History of the Yemen Civil War, 1962 - 68, and others in Stephen Dorril’s big history of MI6. The latter is especially good for a British perspective on the Yemen crisis—and it illustrates how, in the final months of Kennedy’s presidency, the CIA and MI6 shook off the mandates of their respective governments in order to pursue their own independent foreign policy and military interventions.

Here’s the longer answer:

Prior to the mid-1950s, concern with Yemen was almost entirely absent from the foreign policy machine—a curious oversight, given the high presence of the so-called ‘Arabists’ in institutions lik the CIA. The State Department and the Foreign Services did not maintain consistent diplomatic posts in the country, and even the Agency itself held the place in a kind of blindspot. There’s an anecdote, recounted by Orkaby in Beyond the Arab Cold War, that when Allen Dulles himself claimed to have “never even heard” of Yemen nor its ruler, Iman Ahman bin Yahya. Similar attitudes prevailed in the UK. Yemen was regarded as a backwater, a vast tract of underdeveloped land that played second fiddle to geopolitical hotspots like Saudi Arabia (with its incredibly rich and fairly accessible oil reserves, royalist government and inclinations towards a staunch anti-communism) and Nasser’s Egypt (which tended to waver back and forth in its orientation to the East and West).

Both the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China thought quite differently. Yemen was divided into two halves, North Yemen and South Yemen—their unification would not take place until the end of the Cold War, in May of 1990—and the communist world played actively in both zones. Most important was the massive Soviet investment into Hodeidah, a geopolitically-significant city sitting on North Yemen’s western point, right on the shores of the Red Sea. The Soviets poured money, personnel, equipment and raw materials into Hodeidah in order to construct a sophisticated and modern seaport; this allowed them to gain a foothold over the primary oceanic transport routes for crude oil—and, from the eyes of the West, obtain an important node for military operations. They also built roads and airports, manufacturing plants and provided aid with electrical infrastructure. Capital for development was on the agenda too: both the Soviets and the Chinese were the principle lenders to Yemen prior to 1970.

The Soviet movement into Yemen can be contextualized in their wider Middle East and North Africa policy, which was ignited under Stalin and flourished in the Khrushchev years. Technical cooperation agreements with Algeria and Egypt had been struck, which allowed for the open transfer of Soviet technology and resources into those countries (technology transfers would later become a point of emphasis for the Non-Aligned Movement, of which Algeria was a key leader). The trade relationship between the Soviets and the Egyptians was voluminous; the flow of goods between the two increased at an almost exponential rate year after year, and by 1956 the Soviet Union was Egypt’s largest trading partner. In Iraq, the Soviets built plants for the construction of electrical motors and agricultural machinery, aided in developing the country’s nationalized oil fields, and played a key role in the laborious building of nation-wide railroad systems.

For the U.S., the UK and their Gulf state allies, this was a growing problem: the entire MENA region appeared, by the mid-1950s, to be drifting closer and closer into the Soviet zone.

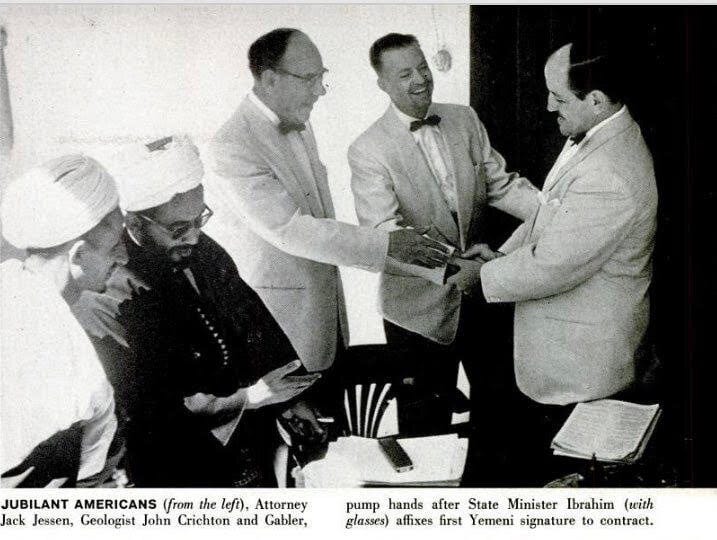

Hence the move to funnel American capital, equipment, personnel, and intelligence operatives into North Yemen by way of the Yemen Development Corporation (YDC). As mentioned in ‘Dark Circuits’, the YDC was headed by OSS-CIA operative—and future JFK assassination conspirator—Jack Crichton, 50% of the YDC was owned by the Empire Trust Company by way of its Oil & Gas Property Management subsidiary. I’ve never been able to pin down who owned the other 50%, but maybe an important clue comes from the presence of George E. Allen, a somewhat notorious Washington D.C. operator and fixer, at the high levels of the company.

At the time Allen was serving on the board of the Atlas Corporation, a major holding company that had been deeply invested in natural resources, aviation, manufacturing, and banking. Back at the end of the Second World War Atlas had been an investor into the ever-mysterious (and intelligence community-linked) World Commerce Corporation, and L. Boyd Hatch—brother-in-law of Atlas Corp. founder Floyd Odlum—had a spot on the company’s board. Atlas was also an investor into Canada’s Argus Corporation, and I touched on Argus’ own relationship to the World Commerce Corporation network in ‘The Empire’s Green Fabric’.

The YDC struck a deal with North Yemen’s Imam in November of 1956 (Orkaby says 1955, but 1956 is the year identified by oil industry publications of the time), with a 30-year lease agreement to explore and pump oil from some 40,000 square miles of land north of Hodeidah—the site of the Soviet-constructed port. Under the terms, the Imam would receive 50% of the profits generated by the YDC, the formation of a sort of dependency structure between his royalist government and Washington.

But the YDC gambit was met with failure. The landscape was remote and inaccessible, the country still lacking the degree of infrastructural development necessary to pull such an operation off. YDC required outside capital and hoped to court one of the oil majors, a Standard Oil or two, into a partnership, but few companies bit. If you peruse the CIA’s CREST database you’ll find a lot of declassified memos and meeting minutes where Allen Dulles, Charles Cabell and other archons of the Agency in its heyday brooded over the apparent impossibility of moving the YDC forward. By 1957, just a year after its launch, the YDC was a failure, and its investors began to drop out.

According to Orkaby, the stake held by companies like Empire Trust was shuffled off to something called Resource Associates Ltd. (this is also reflected in the oil industry publications of the time), which they claim counted future CIA director William Casey had invested into. I haven’t been able to verify this, but Casey at the time was neck-deep in CIA front companies and covert activities. He was also, by 1959, holding stock in Oil & Gas Property Management, the Empire Trust subsidiary that Crichton was running.

In 1960, a very strange man named William Dalzell turned up as acting as an agent of Yemen within the U.S.; his business was traveling around to “make contacts with representatives of oil companies to market” Yemeni oil concessions. Dalzell’s background was peculiar: he had studied “Diplomatic Foreign Relations and Languages” at Georgetown University in D.C. from 1950 through 1953, and popped up at the end of the decade working in mid-level positions in various oil companies.

Like the YDC, Dalzell’s efforts to drum up oil biz for Yemen were doomed to failure. But there’s another similiarity between the two: if Crichton is one link between Yemen and the eventual assassination of JFK, Dalzell is another. Dalzell lived in New Orleans, where he worked closely with the CIA-backed Cuban exile groups being trained in the swamps and forests for an invasion of Cuba. He was also tight with Guy Banister, the FBI veteran and New Orleans private detective that had contact with Lee Harvey Oswald. It was New Orleans DA Jim Garrison who pursued Banister and his associates as the most visible tendrils of the assassination plot; he also glommed onto Dalzell himself, though little came of it.

There may have been a connection between Crichton’s YDC and Dalzell’s latter efforts on behalf of the North Yemen government. A declassified FBI file shows that the bureau met with Dalzell in autumn of 1959 (shortly before he was officially affiliated with the royalist government), and that Dalzell had brought Yemen to their attention—even mentioning Jack Crichton, George Allen, and the Yemen Development Corporation:

After the respective failures of the YDC and Dalzell, the Americans faced yet another set-back. The next suitor to Yemen’s oilfields was John Mecom, the president of Mecom Oil; he gained his concession from the Imam in April of 1961. While this venture yielded little fruit, this exploration effort was yet another example of Washington’s efforts to gain a foothold in the country: Mecom’s work was sponsored by the American Overseas Investment Corporation, which was liaisoning closely with the State Department. Mecom took his work even closer to the geopolitical hotspots than the YDC did. He set up operations roughly thirty miles from the Soviets busy at the Hodeidah seaport.

Something that is interesting is that John Mecom, like William Dalzell, was a New Orleans native. Was there a connection between Dalzell and Mecom? In 1964 the FBI, chasing leads in the aftermath of the JFK assassination, raised the question of Yemen to W. Angie Smith, an officer in Mecom Oil. Smith told the FBI that Dalzell’s name was “vaguely familiar” but was “unable to recall why the name is recalled by him”. Smith stated that he checked Mecom Oil company files for anything relating to Dalzell, but found nothing.

There’s a whole, whole lot more to say about this Yemen nexus—soon the geopolitical tensions would rupture into a long-burning and violent civil war, complete with mercenary soldiers, intelligence operatives, and vast amounts of armaments flowing into North and South Yemen. The substrate of the CIA, the State Department, and their cronies in the oil industry would help deliver to the Arabian peninsula a conflagration that would shake the foundations of the region’s balance of power, and perhaps even changed the course of American politics.

But the work day beckons so I need to wrap this up for now, and return to all of that in a future post.