Late Marxism: Adorno or the Persistence of the Dialectic—Frederic Jameson—I didn’t begin in November, but finished it this month, so it counts. The Adorno that Jameson writes about here is very much Jameson’s Adorno, so don’t expect a straightforward recounting of the infamous grump’s philosophy. It’s ‘Adorno read for the Nineties’, so it’s a bit funny to read it on the cusp of 2025. As always, the thought and their transmutations into words on a page meander and slide about; Jameson was never able to write linearly, which is a good thing. Tangents beget tangents, entire lines of argument are eclipsed by other, more interesting observations and only resume later (if at all). I like that a lot.

Jameson’s reading of Adorno—or at least how I read Jameson reading Adorno—turns about on two points. The first is on the importance of totality, both as a conceptual edifice and operative abstraction at work in the world. When the book was written (and this might be very true for today as well), notions of totality were/are excessively unfashionable, treated either as something that simply didn’t exist or, in a more anarchist register, a force that can be wished away. But Jameson, speaking through his Adorno-mask, reiterates the classically Marxian emphasis on the existence of the social totality, without which we cannot even be able to talk of things like capitalism as a historical plane that mediates social relations.

The other point is the problematic relationship between the universal and the particular. For Jameson-Adorno, the presentation of the universal/particular in Hegel effectively subordinates or enslaves the particular to the universal; it remains trapped within the overarching framework that the universal imposes (there is funny echo here of the very critique of notions of totality of which Jameson is otherwise critical). Properly understood, the two should refract through one another, the universal expressing the particular in and of itself, and the particular, despite its singularity, expressing the universal. But what’s more is that, alongside this mutually-reinforcing dynamic, is that the two are equally independent from one another.

This is the same problem that Jameson returns to elsewhere, both Archaeologies of the Future and the wonderful universal army essay—squaring the circle of communism itself seems to be, in his eyes, the proper reconciliation of the universal/particular problem. It might also bring to mind the Deleuze of Difference & Repetition, which he attempts to grapple with an approach to difference that liberates it from comparison in order to distinguish itself (the metrics of comparison here taking the place of the universal). Maybe that’s why Jameson is constantly trending, but always stopping short of, lifting Adorno into the pantheon of poststructuralist theory.

What’s the point of reading a wandering tome on Adorno written for the 1990s? One could hazard the suggestion that both the question of social totality is as immediately relevant than it ever has been, as the future unfurling of the world system hangs in balance. And at the same time, the universal/particular dialect could easily inform our understanding of ‘multipolarity’, if this now somewhat-cliched buzzword could be understood as an active force in history, a possible outcome of the generalized catastrophe of the present.

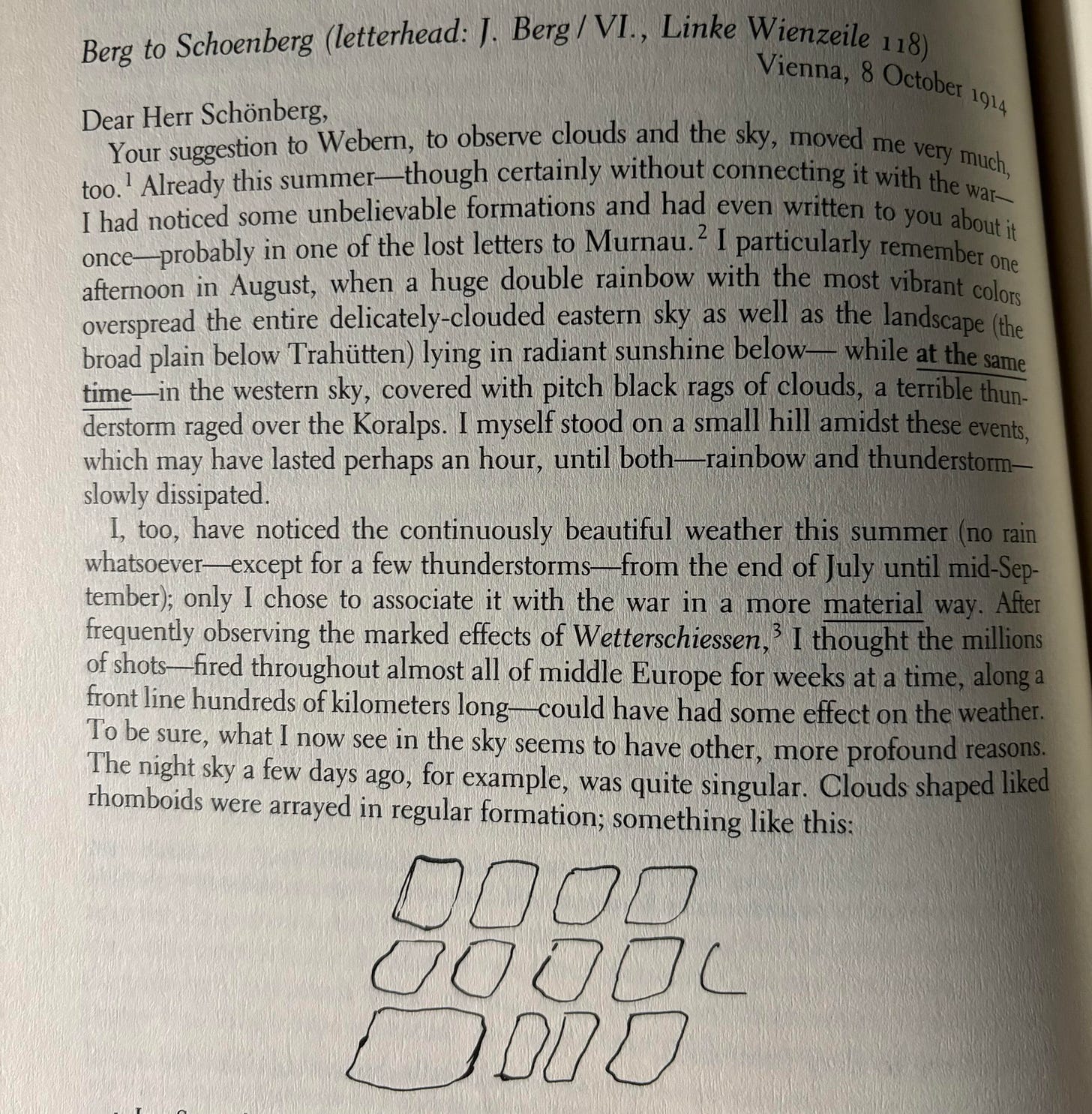

The Berg-Schoenberg Correspondence: Selected Letters—Ok, so I didn’t read the whole thing, which are the letters between the composer Schoenberg and his student, Alban Berg, but I did read a serious chunk of it, albeit by skipping here and there, plucking letters and smaller passages at random. I was charmed and made a little melancholic by Alban’s constant need to impress his teacher, forever trying out different tactics to get his attention, to make amends for what Schoenberg perceived to be his shortcomings. The best parts were the letters from Alban describing how he would stand in Austria’s mountain vistas, staring into the sky to trace the shape of clouds into his memory (he would then commit them to little diagrams, dispatched to Schoenberg), all the while thinking of the relentless pulse of gunfire from the infernos of World War I still raging. Here’s a picture:

There is quite a bit of war gossip that comes through in the Berg/Schoenberg letters, and it is funny how the conflict was in such geographical proximity, but seemed so psychically distant nonetheless.

The Hour of the Star—Clarice Lispector—the Star is the 17th card in traditional tarot deck. It’s a creature of opposites: according to A.E. Waite, the Star can be read as signaling loss and privation, or it can herald hope and rising prospects. The Star represents Aquarius, which makes sense because the water jug that Aquarius carries in astrological symbolism contains both great knowledge and burdens.

I do not know if Lispector intended for this invocation of tarot imagery in the title—early in the book she writes “don’t expect stars in what is coming: nothing will twinkle”—but the climax of the book does concern a tarot reading (we don’t know which cards were drawn). The Hour tells the story of a lowly girl living in the slums of Rio, drawn so far down that she was born at degree zero itself: an impoverished and shattered existence, with nothing but emptiness within her. Yet in these plains of exterior and interior desertion she is sanctified by Lispector, depicted as having achieved a state of unwavering grace like some holy figure. The girl knows no past, no future, but persists in a state of humble freedom nonetheless.

Until the end. That’s when the encounter with the fortune teller takes place and the girl learns that she has a future, that she will find love with a wealthy foreigner named Hans. Infinite possibilities are unlocked—then she steps from the mystic’s parlor, dizzy with enthusiasm, and is struck by a Mercedes. She dies crumpled in the street, her eyes affixed to blades of grass rising from the gutter. Great little book, beautiful and cruel.

“All the world began with a yes. One molecule said yes to another molecule and life was born. But before prehistory there was the prehistory of prehistory and there was the never and there was the yes. It was ever so. I don’t know why, but I do know the universe never began”. “Porous material, one day I shall live here in the life of a molecule with its possible bang of atoms”. “…what I write is a moist fog. Words are sounds transfused with unequal shadows that intersect, stalactites, lace, transfigured organ music”. “I never forgot her: you never forget the person you slept with. The event remains tattooed with a fiery mark on living flesh and all who glimpse the stigma flee in horror”. “If the girl knew that my own joy comes from my deepest sadness and that sadness was a failed joy”. “At this very moment Macabea feels a deep nausea in her stomach and almost vomited, she wanted to vomit something that wasn’t her body, to vomit something luminous. A thousand-pointed star”—a star arrives in the pages of the book after all.

Now I’m reading Lispector’s The Apple in the Dark, per the recommendation of Thomas Murphy, who was recommended the book by somebody else.

The Theory of the Novel—Lukacs—I’m not really interested at all in Lukacs the doctrinaire Marxist, the Lukacs of class struggle and class consciousness, but in the young Lukacs, the one who gave over to the great temptation of his historical moment, Romanticism, and embraced it whole-heartedly to mourn a dejected world and express that interior anguish in this strange little tome on the novel.

What can I say about it? Maybe the best part of the work is early on, that discussion on the Greek epic—right in line with his Romantic impulses, Lukacs presents the epic as presenting a total world, one in which meaning was not only grasped with immediacy but coincided absolutely with everyday life. This was expressed, by Homer and other, in the form of the epic hero—but then came the Fall, arriving in the form of double, yet unified divergence. Through Plato, the “creative act of philosophy” arrived in the tumult of history, cleaving the world in two and shattering this mythic and primordial totality (think of the imposition of the subject/object divide). This is registered in the passage from the heroic epic to the tragic: “[philosophy] had revealed tragic destiny as the cruel and senseless arbitrariness of the empirical”/“the tragic hero takes over from Homer’s living man”.

Lukacs positions the post-Kantian moment (the rise of positivism and scientific exploitation, or instrumental rationality if you prefer that) as the far end of this trajectory. It’s my favorite passage of the book: “Kant’s starry firmament now shines only in the dark night of pure cognition, it no longer lights any solitary wanderer’s path (for to be a man in the new world is to be solitary)”.

The novel grapples with this situation, it seeks to locate the concealed totality that structures our world—here we’re speaking, of course, of bourgeois civilization, which Lukacs drapes in a sense of Biblical dread. “The novel is the epic of a world that has been abandoned by God”. For Lukacs, the world is drenched in meaning, but access to that meaning is an act that fundamentally barred to us (‘meaning’ here converging with Kant’s prohibition on fully grasping the noumenal realm). Because of this, the novel, even those committed to realism, can only operate from the basis of abstraction, though they rebel against this by nonetheless attempting to constitute meaning through the plunge into the depths to excavate the totality.

Neat book. Worth keeping in mind that abstraction as such—concept sheared down unto itself—corresponds directly with the prying loose of populations from their ground, from which meaning is derived, by their transformation into the proletarian class. No wonder Lukacs had to make a hard Marxist turn after this work: to move towards class struggle is the only option left in the impasse at which he arrives.

did Goethes invention of the tower creep you out i know it did me