During a trip to New York last week, I got a chance to stop by and visit—not once but twice—that long-running obsession, spanning the Pseudcast to this blog: the Equitable Trust Building located at 120 Broadway. It’s pretty neat and worth checking out, though don’t expect many facts to come tumbling out from the profoundly disinterested staff manning the small visitor center. The most we were told is that the building is “maybe a hundred years old”; there was little in the way of Bankers Club and its role in the Businessmen Plot against FDR, the connections between Empire Trust and the JFK assassination, the formation of that Temple of High Finance that is the Federal Reserve, the copper cartel, or any of the other machinations that unfurled in the offices stacked above its opulent, marble-adorned lobby.

A few pictures I snapped on my visits:

The trip inspired me to go back and do a little more poking around, to see what might have been missed in the some-four years of deep excavations into the murky history of the Equitable Trust Building. Quite a bit, it seems: as luck would have it 120 Broadway also crosses the subterranean economics of my other favorite subject, the trade of the world’s most mysterious and dark metal commodity—gold.

It was in the very pivotal year of 1939 when the Swiss Bank Corporation—for many years one of Switzerland’s largest private banks, prior to its merger into the ultra-corrupt and shadowy Union Bank of Switzerland—decided to take up residence in the Equitable Building. Part of the arrangements that SBC reached with 120’s owners? The leasing of the vast and hermetically sealed vaults located in the building, which had previously belonged to the Federal Reserve. SBC aimed to use them to hold large quantities of gold and securities.

There is surprisingly little additional information in the way of the gold housed at 120 Broadway—we do not know the quantities nor the ultimate provenance of these reserves, thanks in no small part to the absolute secrecy with which the Swiss circumscribe their central role in the international metal trade. What can be said is that, following the end of the Second World War and the re-emergence of a global gold market, SBC emerged as one of the first major international banks to throw itself into the fray.

There are other, more speculative avenues to explore (and if there is one thing that RC2.0 relishes, it’s unrestrained and perhaps inappropriate speculation). Consider this: at the time that SBC was sequestering gold in New York City, Switzerland was the epicenter of a sweeping and complicated in-flow of huge gold volumes, a deceit-drenched trade Herculean in scale and scope, from Nazi Germany and its Reichsbank.

There were a multitude of ways that this worked, and the techniques honed by the Swiss became the foundation of how the illicit trade in dark gold functions to this day. Sometimes gold, gold certificates and non-gold securities (corporate bonds, stocks and the like) were smuggled into ostensibly neutral Switzerland by German couriers operating under the shielding of diplomatic protection. Much larger quantities of gold were brought in by way of land routes, by train or automobile. Once harbored in Switzerland, the Nazi gold would be re-smelted, fashioned into new bars—often mixed in with gold of non-German origin—and stamped with the seals of the participating banks. Much of the gold would remain in the country, but great amounts were sent overseas, deposited and held by the foreign branches of Swiss banks.

London was a common destination of this gold. Was New York City another?

At the height of the smuggling operation, it was the Swiss National Bank—the country’s central bank—that was the primary recipient of Nazi gold. SNB is estimated to have processed between 85% and 90% of all gold inflows. The remaining 15% to 10% were handled by the largest private and commercial banks in Switzerland. A 1998 report on this gold trade, drafted in connection with the Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation against Swiss Banks, states that between 1940 and 1941, the Swiss Bank Corporation was the largest commercial bank to receive gold from Germany’s Reichsbank.

According to the report, Reichsbank moved $34.9 million worth of gold into SBC during those years. To put this a little bit in context: that’s $705,716,666 worth of gold in 2024 dollars. It isn’t the only time that SBC has involved itself in gold transactions of this magnitude. In 1986 Philippines dictator Ferdinand Marcos moved some 30+ tons of gold—perhaps a portion of the legendary Yamashita’s Gold, the gold stashed in buried in booby-trapped pits across the island by Imperial Japan in the waning days of WW2—into five banks around the world. By 1993 this gold was sold and the profits accrued, totaling around $466 million, were deposited with SBC.

The money was then transferred once again to another Swiss bank, Bank Julius Baer, where it was moved around in multiple accounts for various dummy companies that were set up, in seems, by front-men for Philippine President Ramos—himself now tapping into the occulted gold horde and siphoning it off for himself (Ramos had previously served as chief of staff for Marcos’ armed forces).

Landing somewhere between a twist of fate or the expected order of things, given the high level of unconscious coordination that molds banking capital and finance capital into such a robust, hegemonic system, is that Bank Julius Baer, much like the Swiss Bank Corporation, found itself ensnared into the sweeping probes into Nazi gold smuggling. The bank, in fact, became something of the de facto spokesman for Switzerland’s banking community when it came under fire in the 1990s during the Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation effort.

So did any of the Swiss Bank Corporation’s Nazi gold, once its origins were distorted and obscured, find its way into the gold vaults opened by the bank at 120 Broadway? I dunno. It’s probably impossible to say. Maybe the internal study and report on Reichsbank gold trafficking conducted by the bank in the 1990s could answer this question, but those documents have been sealed away. SBC opted not to share it with the Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation team, and so the contents of the 1998 interim report are admittedly only fragmentary where SBC’s activities are concerned.

Besides the Swiss Bank Corporation, there are other tangled lines running back and forth between 120 Broadway and the Nazi war machine’s economic support apparatus. For many years the Equitable Building acted as the power base for the Harriman family, the dynasty of financiers who controlled (among many other things) the Union Pacific railroad company and the Brown Brothers Harriman investment bank. Harriman family offices were housed at 120 Broadway, and Union Pacific maintained its headquarters there. While Brown Brothers Harriman would ultimately be placed at nearby 59 Wall Street (now re-numbered as 63 Wall Street), the family continued to maintain interests in a number of companies that remained locked at the 120 Broadway location.

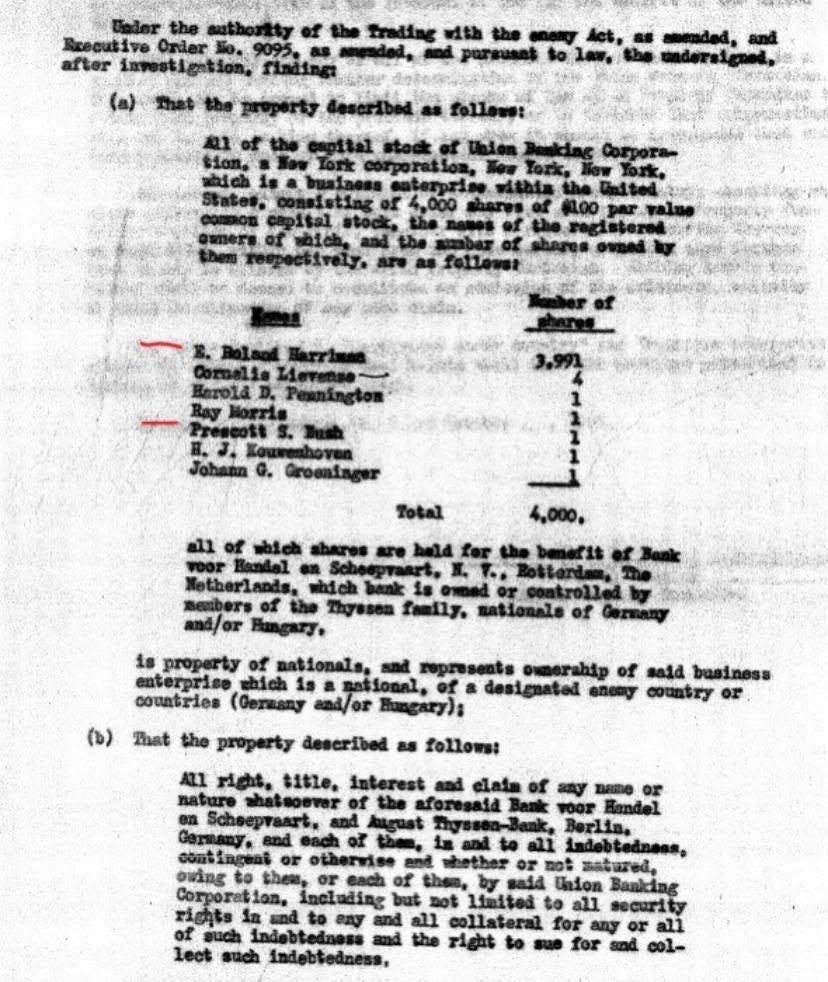

Where this all begins to cross back into German intrigue is that Brown Brothers Harriman owned a stake in a New York-based entity called the Union Banking Corporation, a name somewhat invocative of the Harriman’s holdings in Union Pacific. The dominant shareholder of Union Banking was, however, the Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart N.V—in turn owned by August Thyssen Bank of Germany.

It was the same Thyssen interests, and the industrialist Fritz Thyssen in particular, that emerged as a pivotal players in the bankrolling of the nascent Nazi Party in Germany, and both the Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart N.V. and the Union Banking Corporation that helped grease the wheels with large transfers of money, gold, and raw materials necessary for the formation of Hitler’s machine. This is touched on in Antony Sutton’s book Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler:

Another elusive case of reported financing of Hitler is that of Fritz Thyssen, the German steel magnate who associated himself with the Nazi movement in the early 20s. When interrogated in 1945 under Project Dustbin,11 Thyssen recalled that he was approached in 1923 by General Ludendorf at the time of French evacuation of the Ruhr. Shortly after this meeting Thyssen was introduced to Hitler and provided funds for the Nazis through General Ludendorf. In 1930-1931 Emil Kirdorf approached Thyssen and subsequently sent Rudolf Hess to negotiate further funding for the Nazi Party. This time Thyssen arranged a credit of 250,000 marks at the Bank Voor Handel en Scheepvaart N.V. at 18 Zuidblaak in Rotterdam, Holland, founded in 1918 with H.J. Kouwenhoven and D.C. Schutte as managing partners.12 This bank was a subsidiary of the August Thyssen Bank of Germany (formerly von der Heydt's Bank A.G.). It was Thyssen's personal banking operation, and it was affiliated with the W. A. Harriman financial interests in New York…

Nazi financier Hendrik Jozef Kouwenhoven, Roland Harriman's fellow-director at Union Banking Corporation in New York, was managing director of the Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart N.V. (BHS) of Rotterdam. In 1940 the BHS held approximately $2.2 million assets in the Union Banking Corporation, which in turn did most of its business with BHS.20 In the 1930s Kouwenhoven was also a director of the Vereinigte Stahlwerke A.G., the steel cartel founded with Wall Street funds in the mid-1920s. Like Baron Schroder, he was a prominent Hitler supporter.

Another director of the New York Union Banking Corporation was Johann Groeninger, a German subject with numerous industrial and financial affiliations involving Vereinigte Stahlwerke, the August Thyssen group, and a directorship of August Thyssen Hutte A.G.

As a side note, Antony Sutton was a pretty weird guy. His book on Wall Street and the Nazi Party is a robust work, dense with details, but his other works go to great—and dubious—links to try and frame Wall Street as the motive force behind the Bolshevik Revolution. Nonetheless, he should be noted as maybe the first person to spot the significance of 120 Broadway as a concrescence, an intense compression point, for organized capital in the 20th century. One of his books contains this nifty visual aid:

The ‘Order’ referenced here is, of course, the Skull & Bones Society, which Sutton dubbed “America’s Secret Establishment”.

Anyways, the connection between Union Banking Corporation and Nazi industrial interests led to the bank’s assets being seized by the Office of Alien Property Custodian in 1942, following a lengthy investigation by a Treasury attache named Erwin May. The Alien Property Custodian report on Union Banking, now held in the National Archives, reveals some interesting names:

The above shows how E. Roland Harriman held 3,991 shares in Union Banking, but maybe even more tantalizing is the single share held by Prescott Bush—the father of George H.W. Bush. Prescott had been a partner in Brown Brothers Harriman and a close friend of E. Roland Harriman since their days together at Yale, where they had both been inducted into the Skull & Bones. Prescott would remain with Union Banking for a significant amount of time, and was still affiliated with the bank in 1942 when its assets were seized by the Alien Property Custodian.

In a final twist, there’s the New York City location of the Office of the Alien Property Custodian itself:

you should look into the exchange stabilization fund