Years ago, Kantbot and I put together a long and rambling Pseudcast episode on Newfoundland and Labrador. In many ways I think it’s our best, yet most misunderstood, episode. The research we did is something of which I’m incredibly proud, and the rabbit holes it produced were seemingly infinite in nature, but the sheer volume of information we had marshalled together stretched the ability of the audio format of podcasts to their breaking point. Someday I’d like to revisit that episode’s content and drag the tedium and network analysis that we tried to do there to the page (a small hiccup for this plan: we lost the bulk of our research material through a technical glitch, and I’m simply not sure how one could ever begin to reconstruct it).

The beginning stages of the story are simple enough. We had been tracking the World Commerce Corporation (WCC), the shadowy and ever-misunderstood company, erected before the embers of the Second World War had even cooled, that had been organized by, on the one hand, veterans of the American and British intelligence services, and on the other, an interlinked network of American, British, and Canadian banks and industrial concerns.

The basic mandate of the WCC was two-fold: to begin accumulated key resources and commodities necessary for the new and emergent Cold War bifurcation of the world (and accompany military-industrial and organized social order that this called into existence) and, perhaps more importantly, to circulate U.S. dollars in zones where critical shortages in the currency were occurring. This was to help cement in place the universal empire of the U.S. dollar, reinforced through slick American maneuvering at the Bretton Woods meetings, U.S. Treasury hijinks of all varieties, the rise of the Eurodollar markets, and the later arrival of the petrodollar and petrodollar recycling mechanisms.

Through the cartelization of natural resources, which required effectively stripping the power of sovereign states to manage their own economies, industries, trade relations, and developmental trajectories, and the consolidation of world trade under the dollar, postwar American hegemony was ensured. The WCC was by no means the center of this gambit—there is no true center, only networks and the alignment of competing class factions—but it was an important device in the overall tapestry nonetheless.

We had come to find that the WCC was by no means alone in its work. The company’s principles—people like British spymaster (and entrepreneur invested in can opener technology) William Stephenson, former FDR Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, businessman and OSS operative (and rumored CIA station chief in Madrid) Frank Ryan, Canadian businessman and technocrat E.P. Taylor, etc etc.—had organized ‘adjunct’ companies that interlocked heavily with the WCC and worked closely with it in far-flung corners of the globe. WCC adjuncts popped up in Liberia, Morocco and the Philippines, and plans were in motion to establish them in Ethiopia, Yemen—basically anywhere in the developing world where the political alignment of the growing anti-colonialism movement was an open question.

At least two were established in the Canadian territories. The first was the Argus Corporation, a sprawling corporate conglomerate that had financial holdings in everything from mining to agricultural equipment manufacturing to soda pop. The other was the Newfoundland & Labrador Company. NALCO, as this company was most commonly known, was ostensibly intended to help aid Newfoundland and Labrador’ industrial development program, as envisioned by the province’s pseudo-socialist premier Joey Smallwood. What NALCO really was about was prying open the province’s natural resources to the wider circuits of American, British, and Canadian capital: development stripped of all of Smallwood’s socialist pretense, and rerouted into the maintenance of hegemonic expansion.

We further discovered that many of the key players in the WCC-NALCO axis had spent the years of WW2 working under the American-born Canadian engineer, businessman, and politician C.D. Howe. Howe had been the Minister of Munitions and Supply. This department of the Canadian government wasn’t simply about providing armaments and tools for the war effort: it was effectively a central planning body that took control of the disparate strands of domestic Canadian industry and brought them together into a streamlined, ‘rational’ logistical system.

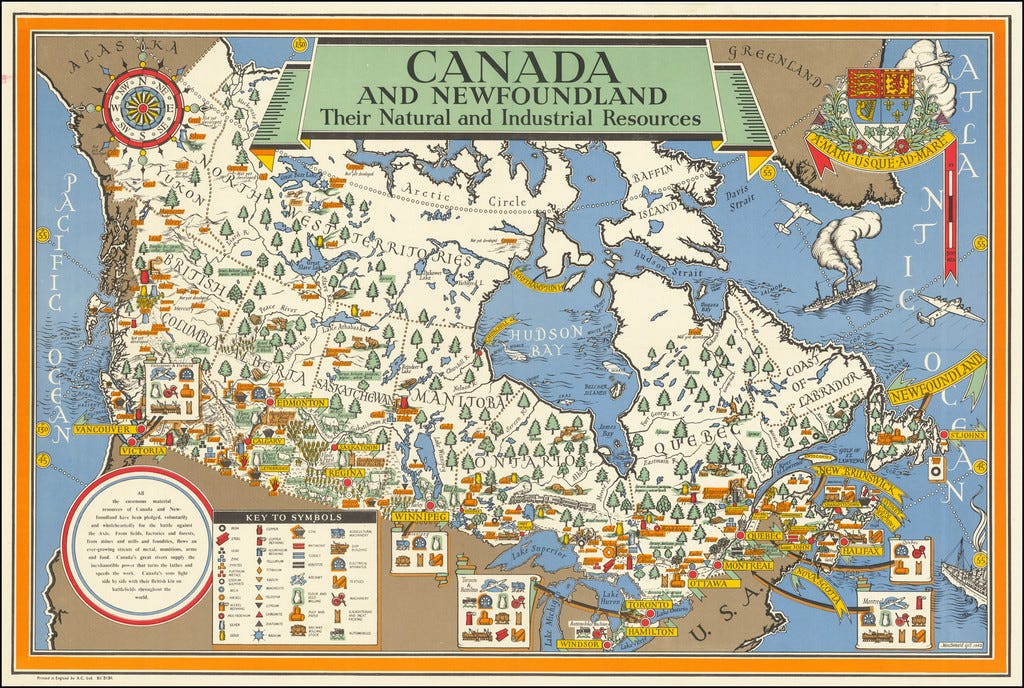

Howe’s efforts also greatly emphasized Canadia’s sprawling natural resource reserves, much of which was scattered across the remote and undeveloped vistas of the Canadian north. Key here was oil, gold, wood, and most importantly uranium—Howe was the Canadian representative to something called the Combined Development Trust, a joint venture with the Americans and British (and which boasted several key personnel, like British spook and banker Charles Hambro, who later joined up with the WCC). Despite its rather innocuous-sounding name, the Combined Development Trust’s intended goal was global in scope: to locate, take control of, and extract uranium reserves on a worldwide level.

Canadian capital is all about the cartelization of the world’s natural resources. It’s almost a misnomer to speak of Canadian capital at all: as great books like The Anatomy of Big Business make clear, at every level Canadian capital is underpinned by the great flows and complicated corporate holdings of American, British, and Belgian (that most evil of countries) banking and industrial giants. And that brings us to this present post, a massive chunk of text from journalist Elaine Dewar’s exceedingly hard to find—and expensive, with copies on Amazon ranging from $150 - $250—book Cloak of Green.

I was reminded of Dewar’s work when putting together my previous post. There, I had touched on the Arizona-Colorado Land and Cattle Company (AZL), which appears as an early example of the recycling of petrodollars from the Saudis into U.S. business—the owner of AZL from about 1974 onwards was Adnan Khashoggi, the famed Saudi arms dealer and insider to the court of their royal family. During the year firsts of the 1980s Khashoggi and AZL plummeted into an impossible-to-untangle series of deals that look a lot like some sort of intelligence operation, and at the center of this deal was a Canadian businessman, politician, and U.N. operative by the name of Maurice Strong.

For those who are old enough to remember, Strong emerged as something of a boogey-man for right-wingers during the Obama years. Glenn Beck, Fox New’s resident goofball at the time, went as far to run a segment accusing Strong of conspiring to collapse the industrialized world in order to consolidate power in the hands of a global government. This is because, from his long standing succession of posts at the United Nations, Strong was the driver of a technocratically-inclined, high-managerial form of environmentalism: he’s often regarded as the “father of sustainable development”.

Elaine Dewar’s Cloak of Green dedicates two sprawling chapters to Strong, fleshing out his background and dissecting the panopoly of arcane business deals, government appointments, and globe-trotting adventures that took place along his rise as the world’s foremost proponent of the ‘green agenda’. What she reveals is something quite odd for an environmentalist of his caliber: his entire background is rooted in natural resource extraction, with a key focus on oil, and that this emphasis never once disappeared as he moved upwards through the levers of global power through the promotion of his message.

Dewar also shows that there is another side of Strong’s business and political acumen. He had an uncanny ability to forever turn up in countries undergoing political destabilization, where revolutions and civil wars were breaking out. He organized quasi-private intelligence networks that had one foot in and one foot out of the Canadian government. He courted politicians in the developed and developing world alike, peddled influence, made contacts, moved money around the globe with ease, structuring government bureaucracies and private companies alike in ways that hid their true functioning. He consorted with arms dealers, dictators, law firms tied to powerful dynasties and spies.

What Cloak of Green shows is that looming behind ‘sustainable development’ is something quite different. It’s the green face masking a naked neo-colonial drive, another iteration of the Great Game. (That Strong became a U.N. technocrat when he did is probably essential: as will be outlined in a near-future post, the 1970s saw a practical battle over the soul of this organization, the developed world versus the Non-Aligned Movement in a fight to determine how sovereignty, international law, and economic autonomy all intermeshed. Needless to say the former won and the latter so unfortunately lost.)

Readers of this blog, and listeners to Pseudcast, will recognize a lot of names that Dewar drops in her biography of Strong. The Hudson’s Bay Company, that longtime British imperial outpost in Canada, is there, and so is—as always—the Empire Trust Company. The aforementioned C.D. Howe makes an appearance, and there is a strong fingerprint of the Bronfman family (keep in mind that not only did the Bronfmans hold a major stake in Empire Trust, but they made a lot of money through contracts with Hudson’s Bay). You’ll see Strong organizing his intelligence network through the Canadian ‘engineering’ firm SNC-Lavalin, so it’s good to keep in mind that a scandal involving this company almost blew up the government of Justin Trudeau just a few years back. Justin’s father, Pierre Trudeau, features fairly prominently in Dewar’s analysis.

There’s a whole lot of Rockefeller stuff too, which is always fun, and a host of less-known names. There’s Ken Good who, like I mentioned in my previous post, got $15 million out the Strong-organized deal around AZL immediately before Good became the benefactor of Neil Bush (these are the connections that laid the groundwork for the CIA-led looting of Silverado S&L). There’s also Jean-Pierre Francois, and this brings us full circle a bit. Francois, always described in the press as an international man of mystery, was of great interest to us in the Newfoundland episode for his dealings with Canadian Javelin, the rather shady company that took control of the Newfoundland & Labrador Company after the WCC entities that set NALCO up stepped back (for the interested reader who wants to pull on some truly strange Canadian Javelin threads, I refer them to pages 200-201 of the late Hank Albarelli’s book Coup in Dallas).

Who or what was Jean Pierre-Francois? We could never never nail him down, but press reports linked him to the mafia, the P2 Masonic lodge in Italy, to the Cagoule terrorist networks, to Pakistani arms deals, and to the Vichy regime in wartime France. Just another long shadow in the deep history of sustainable development.

Anyways, here’s Elaine Dewar’s text:

The Honourable Poor Boy

Strong’s staff had sent me his curriculum vitae. His tower of hats made Elizabeth May’s look pathetic. He listed so many businesses, honours, and NGO involvements, it was impossible to understand how one man could do so much. At first his curriculum vitae also struck me as odd, as if it was designed to sell a life, not as if a life had produced the document. When I had checked it and reviewed it, it also seemed to mirror the patterns of the Global Governance Agenda—NGOs, governments, politicians, native peoples, Marxists, Maoists, and democrats tied in knots with power companies and other great trade empires. His cv was a record of a lifetime of arrangements.

He was born in Oak Lake, Manitoba, in 1929, had only a grade 11 formal education, but had been granted 27 honorary degrees from universities around the world. (The latest count is 35.) He had combined private, public and non-profit ventures at several points in his career, giving rise to questions about conflicts of interest, but as one of his protégés, the writer John Ralston Saul, liked to put it, there was nothing in this that would have startled anyone in the U.S. establishment. That master of the golden braid, John J. McCloy, the man biographer Kai Bird credits with the creation of the national security apparatus of the U.S., had done such things for almost a century.

Many of Strong’s non-profit associates were also participants in the Agenda, either as advocates or as funders of advocates. Strong had been a trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation; a director of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources in Gland, Switzerland; a director and vice-president of the World Wide Fund for Nature in Switzerland; a director of the Beijer Institute of the Swedish Academy of Sciences (now a separate NGO called the International Institute for Environmental Technology and Management); the Aspen Institute; the Bretton Woods Committee of Washington, D.C. He’d been on that particular board since April 1985. The Bretton Woods Committee was formed to promote the virtues of the international development banks after Bramble, Rich, et al came close to beating a U.S. administration-backed appropriations vote in 1984. Strong had also worked with the YMCA; the Vatican’s Society for Development, Justice and Peace; the North/South Institute; the Club of Rome; the Interaction Policy Board. Perhaps most important, he was chair of the World Economic Forum.

…

In July 1943, fourteen-year-old Maurice Strong ran away from Oak Lake. Canada and the U.S.S.R. had become allies. In the previous month the National Council for Soviet-Canadian Friendship had been formed at a huge rally in Toronto which was addressed by Prime Minister Mackenzie King. Brandon, Manitoba soon had its own chapter of this council (headed by someone the RCMP said was a communist who’d been ejected by the CCF as an infiltrator). The Liberal Party and the Communist Party in Ontario had also joined forces to keep working-class ridings from going CCF in the August provincial election. It was in this strange, changeable, and exciting political climate that Strong headed straight for southern Ontario. Strong doctored an identity card to make himself older and jumped a train for the Lakehead, where he stowed away on a Great Lakes vessel. He was found at Windsor. He signed on as crew, got off at Sarnia. Then he headed west on another train. By September, he was in Victoria. He signed on a Canadian Pacific ship transporting U.S. troops up the coast to Alaska. The police were waiting for him when he docked in Vancouver. His father came out to bring him home and begged him to finish school. He got his grade eleven in 1945, and in July, while the war still raged in the Pacific, he boarded the Hudson’s Bay Company’s schooner, the Fort Severn, at Churchill heading for duty as an apprentice fur trader at Chesterfield Inlet on Hudson Bay.

The Hudson’s Bay Company trading post consisted of a manager, an apprentice, and an Inuit helper. The town consisted of a small hospital, a tiny RCMP station, a Department of Transport radio station, and a Catholic mission run by priests from Belgium. The Hudson’s Bay Company owned mineral rights to large stretches of the Canadian north. One of Strong’s tasks was to take the samples of minerals brought in by the Inuit or others and send them south. The Hudson’s Bay Company boats took these samples out from the various posts scattered around the Bay or the RCAF flew packages south from their base at Baker Lake at the far western end of the inlet. In his spare time, Strong and a young Department of Transport worker, Norman Sanders of Toronto, travelled around taking pictures of the Inuit in their communities scattered across the ice.

The militarization of the Canadian north had just begun the year Strong arrived. In 1944, when C.D. Howe was federal minister of munitions and supply, Canadian and allied militaries became interested in the north both as a potential path for invasion and as a future strategic resource basin. That winter, the Canadian Army ran an elaborate defence game out of northern Saskatchewan, making use of the topographical knowledge of the Hudson’s Bay Company trader in the area. In the early months of 1946 the army launched an overland trek of men and machines called Operation Musk Ox. A small group of soldiers took off from Churchill on motorized vehicles, travelled up the coast, turned overland to Baker Lake, then to the mouth of the Coppermine River, across the Arctic coast, and down through the Mackenzie Valley to Edmonton. Samples were taken from likely mineral outcrops. Aside from establishing Canadian sovereignty over the high Arctic and proving that such terrain could be fought over and defended in winter, uranium may have been one of the things the expedition was looking for.’ Strong’s friend Sanders passed on some of their radio messages to Churchill.

According to Strong, sometime during that summer of 1946 a big handsome man named Bill Richardson also arrived in Chesterfield Inlet. An American from Tennessee, he had married a Canadian woman and enlisted in the RCAF in Ottawa in 1941. “Wild Bill,” as he was soon known in the mining business, told Strong he intended to prospect around Baker Lake near the geological/survey/supply base established there by the RCAF. Strong claimed Richardson came in on the Hudson’s Bay Company boat, but Sanders took the last boat of the season out of Chesterfield and met no one called Bill Richardson. Soon Strong also left Chesterfield Inlet, breaking his five-year contract with the Company. When he arrived in Toronto, he went to see Bill Richardson and asked for a job. Richardson set him up with a Toronto mining promoter and invited Strong to come and live in his home. It was Bill who introduced Strong to the world of oil, gas, big money, and geopolitics.

Richardson’s wife, Mary McColl, and her father, John McColl, took an interest in Strong though he was just a boy. McColl was of the family that had founded the largest oil company in Canada, McColl-Frontenac, in the early part of the century. By 1946, McCollFrontenac appeared to be controlled by the brokerage house Nesbitt Thomson, but in fact, since 1938 it had been secretly controlled by its U.S. investor the Texas Company (later Texaco). By 1946, John McColl had long since ceased to be a large shareholder, but the McColls were socially prominent. This perhaps explains why Wild Bill got away with so many outrageous things. He listed the eighteen-year-old Maurice Strong on the prospectus of his new company, New Horizon Explorations Limited, established in April 1947. Strong was described as one of the “five men of the north” who would help the company prospect by air over the vast Keewatin District. The prospectus claimed Richardson had access to recent RCAF mineral surveys of the whole Arctic—documents surely still classified.

The prospectus was written in the language of the brand new Cold War.’ Canada’s mineral wealth had to be secured against the communist evil rampant on the opposite side of the Arctic Ocean. The prospectus suggested uranium could be found near Baker Lake at the far end of Chesterfield Inlet. (It was, by others.) The prospectus assured investors that if the company found uranium, the government would take over the mine and the company. Yet Strong claimed later that Wild Bill also wrote at this time to Stalin about where the Soviets might find uranium deposits. Somehow, Bill got away with this too, although the U.S. had just cut off even its allies from all nuclear information. Bill also got away with stealing mail from the offices of the National Council for Canadian-Soviet Friendship. The Council patrons included a who’s who of Canadian politics, business, and the arts. Sam Bronfman had been a patron, Paul Martin, M.P. was a patron, the prime minister was a patron. But by the time of its convention held in Ottawa in May 1947, the Gouzenko scandal had burst upon the world. The RCMP had kept tabs on the organization from the beginning, noting in their files each confirmed or suspected Communist Party member who got into an authoritative position. The national director, for example, was well known to them. Paul Nathanson (who would eventually become Strong’s partner), heir to the Famous Players movie distribution fortune, was on the executive as its treasurer. (This fact was seemingly of no interest to the RCMP watchers unless particulars about Nathanson were among the things CSIS removed from the file it finally sent on to me.) The new office of New Horizon Explorations Limited was located right next door to the National Council for Canadian-Soviet Friendship offices. One Saturday, said Strong, Wild Bill just fished out the Council’s mail from under their door and found a list of people he said were Communist Party members. He wrote to the police. Pretending to be prospectors, the police put the council’s rooms under surveillance from Bill’s offices.

So who, or what, was Bill Richardson? Airman, spy, freelance entrepreneur? All of the above? Within a year, New Horizon Explorations Limited was wound up, shares in other mining companies were given to the investors to pay them off, legal niceties handled by John Black Aird, a young lawyer well connected in the Liberal Party who later became Ontario’s lieutenant-governor. Strong said he didn’t really get involved in Bill’s version of the Great Game. “I wasn’t a spy,” he said. “I was too young for that.”

On the other hand, Bill did introduce Strong to some very important persons right after that mail episode. For example, the Honourable Paul Martin, M.P. for Windsor, dropped by the house. Martin had acted as a lawyer for Paul Nathanson’s father, who had died in 1943; the young Nathanson had also become Martin’s friend. Martin was on the continentalist side of the Liberal Party, along with Prime Minister King, and had become a member of King’s cabinet after the June 1945 election. In December 1946, he had been made both minister of health and welfare and the leader of the Canadian delegation to the U.N. The Partition of Palestine was to be discussed by a U.N. commission in the fall of 1947—a matter of some considerable interest to major oil companies. Strong was introduced to Martin by Richardson. Later, Richardson took Strong to Ottawa and asked Martin to get Strong a job at the U.N. Strong professed fascination with the U.N. since he read a newspaper article about it during his hobo summer of 1943. Martin said he couldn’t help.

Soon another important person dropped by Bill’s house. Noah Monod, then treasurer of the U.N., was from France and of a Huguenot family. Strong was introduced to him too as a young man fascinated with the U.N. who wanted a job there. Monod got him one as assistant pass officer in the Identification Unit of the Security Section and said he might become a clerk on the Palestine Commission.

That is how it happened that in the summer of 1947 Maurice Strong went to New York. He stayed briefly with Monod, where he was also introduced to David Rockefeller, grandson to the man who’d made the oil business global. Rockefeller already had charge of the U.N. account at the Chase Bank.

As Strong remembered it, he said straight out to David Rockefeller, “I’m deeply prejudiced against you and all your family stands for.” Nevertheless, over the next fifty years, Strong became associated with various members of the Rockefeller family. He knew Nelson Rockefeller, who had an intense interest in the development of Latin America; he knows Laurance, who has interests in conservation. But he met David Rockefeller first. David Rockefeller had been an intelligence officer in World War II in North Africa, where using young boys for information was a standard practice. David Rockefeller knew Canada well: he’d been sent by his father, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to meet Mackenzie King in 1935, the year King became prime minister again after a federal election that returned the Liberals to office.

…

Strong started work at the U.N., preparing accreditation cards and passes, on September 15, 1947. He met lots of famous people. Paul Martin saw him there. Strong met Andrei Gromyko, who made the speech for the Soviet Union in favour of creation of the state of Israel. When the U.N. commission recommended that Palestine be split into the state of Israel, Gaza, and Jordan, it was a green light for joint venture oil partners like Socal and the Texas Company, which had exclusive oil concessions in Saudi Arabia. Socal and the Texas Company together owned a joint venture called CalTex which had paid the Saudi king, through his adviser, Kim Philby’s father, a lot of money for these rights. Soon after the commission’s report, McColl-Frontenac’s stock split two for one. It revealed itself later as a company controlled by the Texas Company and announced it would bring the first shipments of oil to Canada from the Middle East.

Two months after he arrived at the U.N., Strong quit, went back to Winnipeg, joined the RCAF, scrubbed out, and then became a trainee analyst at the brokerage firm of James Richardson and Sons. After oil was struck at Leduc, he became an oils analyst in Calgary. There he met Jack Gallagher who’d spent twelve years working for Standard Oil of New Jersey and its Canadian subsidiary, Imperial Oil. Gallagher had just been hired by Dome Mines to build an oil and gas exploration company called Dome Explorations (Western) Limited. Dome Mines was controlled from New York. Henrie Brunie, a close friend of John J. McCloy, was on its board. Dome Explorations raised $7 million through a syndicate led by New York investment banker John Loeb of Lehman Brothers Kuhn Loeb (soon to be Edgar Bronfman’s father-in-law). Investors included Harvard University’s endowment fund and the New York-based Empire Trust, managed by McCloy’s friend Henrie Brunie. Dome Exploration became one of the largest so-called independent oil exploration companies in Canada—but its controlling shareholders were embedded deep in Wall Street with ties to the family who started Standard Oil. By 1951, Strong had married, bought a house, and gone to work at Dome as Gallagher’s assistant. In Gallagher’s memory, Strong was no genius: his most important characteristic was that he had a flexible mind.

In 1952, Strong sold his new house, quit his new job, and travelled with his new wife around the world. His friends thought he must have made a fortune because prairie people, seared by the Depression, often could not bring themselves to walk away from any job. His friends knew he revelled in finding multiple virtues and uses for every course of action he took. Nothing was done for its own sake. So what, one wonders, were the multiple utilities to be found in these travels? It was a difficult time to wander. The Korean War was on and J. Edgar Hoover’s tool, Senator Joseph McCarthy, was attacking the CIA as an institution crawling with communists. Nonetheless, the poor boy from Manitoba set out with his wife.

…

When Strong arrived in Africa, the pre- and post-war colonial governance structures were crumbling and there was a struggle for power and market share among the major oil companies—British, French, and American. They were like bridgeheads for their governments. David Rockefeller was active in Africa: the Rockefellers had made a decision to do business with South Africa in spite of Apartheid, so that meant they had fences to mend among new African leaders as they searched for business opportunities in newly emerging national states on the continent. Often the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, a family philanthropy run by the children of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., was used to pave the way. In Nairobi, Strong got a job with CalTex, the joint venture between the Texas Company and Socal to exploit Saudi oil. His job involved travel. He went to Eritrea, Zanzibar, Tanzania, Uganda, Mauritius, Madagascar, Zaire, a rollcall of places soon to be embroiled in the gilt-edged tyrannies of the Cold War. He stayed in Africa for a year. Then he and his wife hopped freighters home, passing through India, Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Hong Kong, the Philippines until they arrived back in Calgary in December 1954.

Strong then tried to get a job in the Department of External Affairs: he was told he couldn’t even apply without a university degree. So, he said, he decided to use business as a platform, a means to power. He never explained to me what he wanted this power for: it just hung in the steamy Geneva air that he wanted it to pursue the General Good.

He seems to have understood early that power is augmented by influence spread throughout a number of networks. He moved rapidly into three. He not only went back to work at Dome, he also volunteered at the YMCA very quickly after his return, and by 1956 he was already so close to the federal Liberal Party, in the person of federal cabinet minister Paul Martin, that Martin regularly visited Strong’s house when he was in Calgary: Martin was then getting ready to run for the leadership of the Liberal Party.

The YMCA had a worldwide network that crossed Cold War barriers. It was one of the few Western organizations that maintained its facilities in Eastern Europe and mainland China. Strong managed to attend the Y’s 100th anniversary in Paris in the summer of 1955, though he’d only been back in Canada for six months and was a brand new Y volunteer. He detoured to Geneva and introduced himself to his very distant American cousin Robbins Strong. Robbins Strong, like his aunt, Marxist journalist Anna Louise Strong, had spent some of the war years in China. The Y had just appointed him the professional secretary of its extension and intermovement aid division which divvied up government and private money for aid projects. These monies were moved discreetly around the world by the Protestant-owned Swiss banks of Geneva. Léonard Hentsch of the private bank Hentsch et Cie. was the division’s treasurer that year. Strong met Hentsch, too, and they became friends—later partners. Strong told Robbins that he wanted to travel the world as a Y professional based out of Lausanne, that he could work without salary for a year. The Y said no. But Strong found reasons to go back to Switzerland anyway. In due course, the two Strongs formed what Robbins referred to as “a cabal” to reduce U.S. dominance of the Y’s international system. As Robbins saw it, there were problems with the International Committee of the U.S.A. and Canada, which raised funds for work abroad. By 1958, at twenty-nine, Maurice Strong had got himself appointed to that committee and went regularly to New York.

The next year, a worldwide oil glut caused the major oil companies to drop the price they paid at the wellhead for oil, which led to the formation of the OPEC producer’s cartel. Strong picked this time to leave Dome and form his own company, MF Strong Management. Empire Trust, run by McCloy’s friend Brunie, with two reps on its board from Standard Oil of New Jersey and one from Texaco, had a business problem Strong was allowed to fix in Edmonton. Ajax Petroleum, one of their “independent” oil companies, had signed an unfortunate contract. If Strong could get Ajax out of this contract with Imperial Oil, he was promised equity in the company. By 1960 Strong was an equity holder in Ajax, and that summer Paul Martin’s son, Paul Martin, Jr., came out to work for Strong during his vacation from university.

After the election of John F. Kennedy and the disaster of the CIA planned invasion of the Bay of Pigs in Cuba, Cold War tensions heightened. The Rockefellers. and their friends were pushing for a test ban treaty and a rapprochement with the U.S.S.R., as well as European union beginning with the Economic Community. Allen Dulles was dropped as the head of the CIA, and John McCone, on the board of Socal, was appointed the new director of the CIA. (“Did you know McCone?” I asked Strong, at one point in our conversations. “McCone?” he asked. “I knew McCloy,” he corrected.) Kennedy had appointed the Rockefellers’ lawyer John J. McCloy his disarmament commissioner. McCloy held negotiations in Geneva with the U.S.S.R. McCloy tried to inch the U.S. back towards the idea of an international body responsible for global arms policy.

By 1961, Strong had been appointed chair of Robbins Strong’s international division at the Y, which gave Strong a reason to rent a house outside Geneva. Paul Martin, Jr., came to visit Strong there and observe the beginnings of European unification, something strongly supported by the people at the Council on Foreign Relations. That same year, Strong also met Harold Rea, the new president of the Canadian YMCA and a man who ran an oil company controlled by Power Corporation in Montreal. Rea was looking for a new president for Power Corporation.

Power Corporation was a network nodal point for Canadian politicians and their arrangements. It had been put together in 1925, when Mackenzie King was prime minister, to control the ownership of power generation facilities across the country, specifically in Quebec, Manitoba, and British Columbia. Like a junior Octopus, it also held control blocks in many other oil and gas companies. Former and future politicians and political back room boys worked on the staff or served on the board. Control of Power-had been in the hands of Peter Thomson, Sr., head of the Montreal brokerage firm Nesbitt Thomson (the same company that had appeared to control McCollFrontenac when it was actually controlled by the Texas Company). Power Corporation shares were publicly traded, but voting control rested in a block of special preferred shares each of which carried multiple votes. These preferred shares had just passed to Peter N. Thomson, Jr., upon the death of his father. He was only a year older - than Maurice Strong but already a bagman of some note. He was then the treasurer of the Liberal Party of Quebec, which had just edged out the corrupt Union Nationale machine in a tight election.

…

In June 1962, just as Diefenbaker’s Progressive Conservative federal government was reduced to a minority and nationalism exploded in Quebec, Maurice Strong arrived in Montreal as a senior executive of one of the most important companies in the country. He was also a player in the international YMCA network and in the Liberal Party. He described the particular virtues of running Power Corporation. “We controlled many companies, controlled political budgets. We influenced a lot of appointments. ... Politicians got to know you and you them.”

He recruited to Power more young men interested in business and politics many of whom had attended Harvard, the intellectual community he had ties to. He hired James D. Wolfensohn (Harvard MBA) to run the new Australian-based subsidiary called SuperPower International. Wolfensohn went on to a brilliant career on Wall Street, and then created his own firm, James D. Wolfensohn Co., which is presided over by Paul Volker. Strong hired William Turner (Harvard MBA), who followed Strong as president of Power Corporation and crafted the merger of two pulp and paper giants into Consolidated-Bathurst. Strong hired Paul Martin, Jr., who later managed that investment.

After Lester Pearson’s Liberal government came to power in April 1963, Power funded think tanks to make public platforms to sell the political agenda of the new government. Jim Coutts, Pearson’s principal secretary, introduced Strong to Finance Minister Walter Gordon, then proposing a Canadian development corporation to help Canadian companies compete globally. Strong gave speeches in support. Power Corporation’s meetings at Mont Tremblant became semi-public stages to test market the not-yet-widely-known but politically interested, such as Pierre Trudeau (London School of Economics and Harvard).

Strong also began to influence Canadian foreign policy. As part of the thaw after the Cuban missile crisis the Rockefeller interests were pushing for, he led a Canadian YMCA group to the Soviet Union and brought Soviet youth officials back to Canada. In the summer of 1964, while Strong helped Prime Minister Pearson with the creation of the Company of Young Canadians, he also started to criticize the tiny department of External Aid. Fostering Third World development and U.S. business through foreign aid was also part of the Rockefeller agenda. The director general of External Aid reported to the Honourable Paul Martin, Strong’s old friend and Pearson’s minister of External Affairs.

The first entry for Maurice Strong on David Rockefeller’s legendary card index of important contacts indicates that Strong, as the new. president of Power Corporation, attended a Chase investment seminar in Montreal in 1965. That was the year Pierre Trudeau, Gérard Pelletier, and Jean Marchand were elected as federalists from Quebec to change the facts of francophone life in Canada. That was also the year Strong renewed his business acquaintance with Paul Nathanson, Paul Martin’s friend and backer, on the occasion of Paul Martin, Jr.’s, wedding in Windsor. Strong and Nathanson had done business in Calgary in the 1950s and proceeded to do business together again through Power Corporation and in other private ventures. Among the things they tried but failed to do was to set up a third Canadian television network controlled by Power Corporation. Strong also introduced Nathanson to his friend John Wanamaker, then working for Sam Bronfman’s children’s investment vehicle, CEMP.

Soon all these parties were interconnected to each other in so many triangles it was hard to tell where one left off and the other began. Power, Nathanson, and CEMP all tried to take over National General Cinema in the U.S. At the same time, Wanamaker took on the management of External Affairs Minister Paul Martin’s investment portfolio. Martin had already come to own through Nathanson three movie theatres in western Canada, which he leased out in management deals to Paramount Pictures. CEMP tried to buy Paramount Pictures. Paul Martin, Jr., (Harvard Law) then went to work at Power Corporation. Soon the job of director general of external aid opened up: someone, it can’t be recalled who, told Prime Minister Pearson that Maurice Strong was just the man for the job. In June 1966, Strong left Power Corporation to become the director general of external aid, reporting to the minister of external affairs, Paul Martin. Once again, Paul Martin was planning to run for the leadership of the Liberal Party.

Much astonishment was registered in print: why would a man at the top of the business world want to work as an assistant deputy minister for the government of Canada at a piddling salary? Grossly inflated accounts of Strong’s salary at Power were published at this time. The same month he joined External Aid, he also became president of the YMCA of Canada. While working for the federal government in charge of Canada’s foreign aid program, he also pulled the Canadian Y out of its special relationship with the U.S. on the International Committee.

It was a very significant time for Strong to join the top ranks at External Affairs. That was the year External Affairs Minister Paul Martin, at the urging of new M.P.s Pierre Trudeau and Donald MacDonald, moved at the U.N. that it admit both Peking and Taiwan. This had the flavour of a triangular transaction with the Chinese. The Chinese had just entered the turbulent Cultural Revolution: their operatives and networks were being rolled up in Africa. Canada had problems of its own in French Africa. The Liberal cabinet was concerned about Gaullism in France and the role France might play stirring the nationalist pot in Quebec. Letter bombs had begun to explode in mailboxes. There was fear in cabinet that France might entice its former colonial governments in Africa, over which it still wielded great influence, to proffer Quebec a de facto sovereign recognition. There were no Canadian embassies in French Africa. Sharp elbows were needed in back channels. Perhaps African nationalists could be encouraged to avoid contact with their Quebec counterparts?

The committee of cabinet dealing with these issues wanted a flexible fix, something that would soothe Quebec while taking the offensive against foreign manipulation. A layered solution was found. Both could be done through development aid programs for France’s former African colonies. Interestingly, the use of aid in this fashion fit with American policy, which in turn fit in with development policies Nelson Rockefeller had been advocating since the end of World War I. As Rockefeller used to say, it was hard to get rubber out of the Amazon for the Allies from people who were too hungry or sick to work. By 1962, the U.S. had also begun to use the new USAID to back nationalist movements abroad to counter communists.

Strong, as the new director general of external aid, lunched frequently with Prime Minister Lester Pearson, who decided to send his new parliamentary secretary, Pierre Trudeau, to Africa to scout possibilities. Trudeau had last visited China in 1960 and had been a traveller in the Soviet Union in 1951. He knew his way around. Trudeau’s report led to a larger mission headed by Lionel Chevrier, whose orders were to get out there and say yes to whatever French African leaders wanted. Chevrier returned with proposals from Morocco, Tunisia, Cameroon, and others.

It fell to Strong to arrange delivery. Since he had almost no staff at External Aid, he made a deal with SNC (now SNC-Lavalin), a Quebec-based engineering company, to offer “technical facilities” to External Aid in Africa. The terms were simple. SNC would act as _ overall contractor but was not permitted to bid on any of the individual aid contracts let by the government (other companies in Quebec did that). SNC was also required to hire for the field anyone Maurice Strong wanted hired and no one Strong didn’t approve of. (One of those hired later became Canada’s ambassador to the U.S. and also ran Petro-Canada International for ten years.) One of the most successful projects was the construction of a series of microwave towers across northern Africa. These towers permitted African countries to phone each other directly instead of running their communications through France (where they could be listened to).

These odd arrangements between External Aid and SNC were the - root for the government agency CIDA, the Canadian International Development Agency, which Strong created in 1968 to replace External Aid. Before Strong had even finished the legislative framework for CIDA, Prime Minister Pearson, planning to retire, also dreamed up the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), a similar organization to CIDA but more loosely tied to the government. IDRC had a clause in its enabling legislation that allowed it to give money directly to individuals as well as to governments and private organizations. It was set up as a corporation, reporting to Parliament through the minister of external affairs. Its board of governors was designed to include private and even foreign persons. Like a company union, it was a device of the federal government, but it wasn’t actually a part of the government—it can best be described as a governmental organization privatized—a GOP. This legal structure was an inspired way to extend government influence into the private domain, and vice versa, without attracting attention. Since IDRC was not created as an agent of the Crown (as CIDA is), it was able to receive charitable donations from corporations and - individuals as well as government funds. By 1976 it was able to issue charitable tax receipts. Strong became its chairman—in October 1970.

By the time Strong got to the part in his story about how he used SNC as a private front for federal government skullduggery in Africa and Quebec it was Saturday afternoon. He had invited me over to his rented house in Aniers, a village outside Geneva. His house was a plain modern box with French doors opening onto a nice rolling lawn. We sat in his living room. He appeared relaxed. His second wife, Hanne Marstrand, drifted around. She showed little interest in this conversation about SNC and CIDA, as if she’d heard it all before, but it was news to me. I found myself sitting bolt upright. His meaning was quite clear. He had helped create a federally funded but semi-private intelligence/influence network that could have impacts both in Canada and abroad. He later confirmed this interpretation, although he said he had never described it that way before. I was shocked. It had never been acknowledged that Canada had a foreign intelligence or influence capacity outside its embassies. Yet Strong was telling me that he had created one out of virtually nothing. There was no reason to suppose that this network wasn’t still running through CIDA and its cousin IDRC: I had reason to believe it was.

It seemed to me that Strong and the federal cabinet got away with this semi-private intelligence/influence system because he’d hidden what he was doing in plain sight. CIDA, the successor organization to External Aid, made regular reports to Parliament and was audited by the auditor general. It was frequently excoriated for the absurd wastes of its tied-aid practices. CIDA may well be wasteful, but that is surely part of the point of the arrangement. Strong ran federal funds through a Quebec-based engineering company, which gave that group bankability and yet tied it to the federal power. Other Quebec companies also got a large cut of federal largesse through tied-aid programs, meaning the aid recipient had to purchase Canadian products and services. Meanwhile, Strong’s hand-picked people in Africa got private companies to hide behind. While the public works done abroad may not have given much benefit to the poor, they made foreign political actors happy. As Paul Palango would later suggest in his book, Above the Law, some Quebec political leaders were made happy too because they got a cut from these contracts as campaign contributions. Maurice Strong got information and could exert influence.

This whole layered arrangement was also useful to more parties than the government of Canada. Who? Any group with heavy levels of investment or loans outstanding in Quebec who required continued political stability there—parties like the Chase Manhattan Bank, like Empire Trust, which had just merged to become the Bank of New York, like the M.A. Hanna Company. Only four years earlier, M.A. Hanna Company had helped organize a coup to preserve interests in Brazil. Canada and Canadian investments were at least as important to M.A. Hanna as those interests in Brazil.

In 1968, Pierre Trudeau (a man featured at, Power Corporation think tanks) defeated Paul Martin (whose son Paul Martin, Jr., had taken leave from Power Corporation to work on‘his campaign) and Robert Winters (a Power Corporation board member) to become leader of the federal Liberal Party. Strong arranged to be out of the country so he wouldn’t have to choose publicly among these powerful men at the convention. In June, Trudeau won a landslide election preaching about the Just Society and participatory democracy.

In July, after Trudeau became prime minister, Strong got in touch with both the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations. He now reported to Mitchell Sharp, Trudeau’s minister of external affairs:.Sharp had been a trade bureaucrat under C.D. Howe and a senior executive of Brascan. He was a continentalist in trade matters. Strong indicated his willingness to co-operate with Rockefeller and Ford and offered to put his special people in touch with their counterparts at Rockefeller Foundation. He had promised them CIDA funds for a project to join together the Rockefeller and Ford-funded international agricultural research centres in the Philippines, Nigeria, and other countries. However, after a conference of donors in Italy in 1969, Strong wrote the Rockefeller Foundation to say that for certain political reasons related to wheat, CIDA was unable to deliver the money he’d promised. According to a letter about a phone conversation between an officer of CIDA and an officer of the Ford Foundation, sent on to the Rockefeller Foundation, Strong promised to make up the difference through the brand new IDRC’s budget. IDRC offered real advantages as far as Ford and Rockefeller were concerned. It could make its grants direct to individuals without going through foreign government agencies.”

That same year, Strong got a call from the Swedish representative at the U.N. The Swedes had pushed a resolution at the U.N. to hold an international conference on the human environment at Stockholm. Strong said he was asked if he would take over running it. A French person had previously been asked to do it: there were certain difficulties.

Strong’s appointment had always puzzled me. Given his history in the energy business, in which he seemed never to have shown interest in the environment except as something to be used, why him?

Strong explained that when he became active “‘in the international network,” he was seen to have some influence in developing countries. These developing countries, led by Brazil, were resisting the conference. As Senador Passarinho had explained, nationalists in the Brazilian military were convinced this U.N. environment conference was part of a plot to grab Brazilian resources. The Swedes thought Strong could deal with Brazil.

It took a while for Strong to get Trudeau’s permission to take this appointment. Why? Strong said he was busy “recruiting” people for Trudeau. What did he mean by recruiting? He would suggest people for government positions, and mostly Trudeau would taken them on. Strong recruited Jack Austin as Trudeau’s deputy minister of what became Energy Mines and Resources, for example. While finishing these tasks, he hired Jim Coutts, Pearson’s former appointments secretary, to get things going in New York on the Stockholm Conference.

Strong, a federal civil servant, had certain private investments to take care of too. He had been involved throughout his tenure in government in real estate in Toronto through a company called Plural Properties (with Paul Nathanson) and another called M.N.S. Investments, which was one-third owned by former External Affairs Minister Paul Martin, one-third by Nathanson and one-third by Strong. These companies had just taken over and reorganized a Toronto real estate company, renamed Y and R Properties. Ken Rotenberg continued to run the new venture. Strong put CIDA’s new director general of special advisers, John Gustave Bene, a war-time Czech immigrant to Canada, on Y and R’s board. Strong had recruited Bene to manage the special people he’d hired through SNC as they continued their work at CIDA. (Bene later did a similar job at IDRC.) In January 1969, Y and R went public. In the spring of 1969, Paul Martin, now a senator, became Liberal House Leader in the Senate, which made him a member of the government. Strong, Martin, and Nathanson sold some of their Y and R shares at this time.

Strong went to New York both as an undersecretary general of the U.N. reporting to U Thant and as the secretary general of the Stockholm Conference. Plaudits rained upon him: the New Yorker said he might save the world. He was made a trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1971—a position he retained until 1977. The Rockefeller Foundation made a grant for the running of his Stockholm Conference office. He became a member of the Century Club and the Yale Club. He was handed the writing services of Barbara Ward, a British political theorist who promoted the virtues of the one-party states of Africa, and of René Dubos, a French ecologist who’d spent his life working at Rockefeller University.

Around this time, and partly to service the Stockholm Conference, the government of Canada began its practice of funding NGOs. Previously treated as private organizations, charities and other groups opened themselves to the money and policies of the federal government—becoming, in effect, PGOs, private government organizations, while calling themselves NGOs, nongovernmental organizations. It began with Opportunities for Youth grants, then spread through the larger Local Initiatives program. Canada put together a participatory task force to involve various Canadian environment groups and business representatives in its delegation to Stockholm. Strong’s former protégé William Turner, by then president of Power Corporation, went to the Stockholm Conference as an NGO concerned with transportation. Why not? Power Corporation owned Canada Steamship Lines. Shipping owners were worried that there would be a convention signed at Stockholm to require the transport of oil in double-hulled ships. This is when Strong first demonstrated that the phrase NGO could be applied, like a democratic varnish, to dignify any group. This rubric could be applied to private organizations funded by government (PGOs); government organizations privatized (GOPs); three people meeting in a basement; or a highly organized business lobby. By calling them all NGOs, he dignified them as the vox populi.

The Stockholm Conference may also have served as a cover for certain triangular reconfigurations of the global power map. In 1969, as Strong was invited to put the conference together, Canada and China also began to negotiate in secret at Stockholm the resumption of their diplomatic relations. This move also fit with the Rockefeller view of global affairs. In 1968, while running for the Republican presidential nomination, Nelson Rockefeller had argued publicly that the U.S. should open discussions with China. One of Richard Nixon’s first acts as president in 1969 was to order his new national security adviser, Henry Kissinger (a man who had risen to prominence through the Council on Foreign Relations and who was paid a $50,000 tip when he left the Rockefellers’ service to work for Nixon), to get secret talks going with the Chinese. The People’s Republic of China agreed to come to the Stockholm Conference as their first appearance at a U.N. function since the 1949 Revolution. When Strong went to China for discussions, the Chinese took him to see Anna Louise Strong’s grave.

Strong found there was real scope at the U.N. for anyone with his skills. He could raise his own money from whomever he liked, appoint anyone he wanted, control the agenda. He told me he had more unfettered power than a cabinet minister in Ottawa. He was right: no voters had put him in office, he didn’t have to run for re-election, yet he could profoundly affect many lives.

Just as he had done at Power Corporation, he used the U.N. as a public platform from which to promote certain ideas. Barbara Ward and René Dubos co-wrote Only One Earth, a paean to the idea of globalism. They published it themselves and stuck a U.N. logo on it. Dr. Carroll Wilson of the Sloan School of Business (later the holder of the Mitsubishi chair at the school) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology sent his protégé Bill Matthews, a systems analyst, to Strong. He also organized think tanks for Strong at MIT. Established conservation groups like the Sierra Club developed new international committees, as did Friends of the Earth, then a brand new organization.

As the Stockholm Conference opened in 1972, Strong warned urgently about the onset of global warming, the devastation of forests, the loss of biodiversity, the polluted oceans, and the population time bomb. He suggested a tax on the movement of every barrel of oil and the use of these funds to create a large U.N. bureaucracy to blow the whistle on pollution wherever it was found. As I read this old speech, I realized it could almost be repeated at the Rio Summit. How could the same issues be on the table twenty years later? A Greenpeace document, circulating before Rio, alleged that the Stockholm Conference was a failure because of what was not discussed. Certainly for some the limited discussions constituted failure. For other interests, they constituted success.

After Stockholm, some Western countries followed the U.S. lead and set up new departments of the environment and passed laws and regulations. Environment issues became part of various national governments’ administrative frameworks. The public process of environmental impact assessments in the U.S. became identified in the public mind with a new meaning of democracy—the right of affected parties to group together and be heard before public land use decisions are made.

The other by-product of the conference was the creation of a new U.N. bureaucracy, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). Like so many of the organizations Strong has made, this one too had multiple uses. In 1974, UNEP rose out of the undeveloped soil of Nairobi, Kenya, Strong’s old stomping ground. Placing UNEP in Africa was explained as a sop to the developing countries, who had been suspicious of Western intentions. But it was also useful for the big powers to have another international organization in Nairobi. After the Yom Kippur War in 1973, Nairobi became the key spy capital of Africa. Strong became UNEP’s first executive director.

Right after the Yom Kippur War, OPEC raised prices 70 per cent and placed an embargo on those states that had sided with Israel. Aramco, the consortium extracting Saudi oil, enforced it: the major. oil companies claimed that they weren’t behaving as a cartel by choice—foreign governments made them do it. When supply was curtailed by major oil companies to the eastern half of Canada at the beginning of the winter, to alleviate public concern and suspicion of oil company motives, Pierre Trudeau’s minority government announced its intent to create a national oil company. Stories then appeared in various newspapers describing certain financial arrangements among Liberals in office. It was a bad time for political leaders to be seen to have had help from corporate interests. The Watergate hearings, which delved hard into relations between corporations and the campaign to re-elect Richard Nixon, had an avid television audience.

The newspapers pointed out that Paul Martin (Trudeau’s leader in the Senate), Jack Austin (Trudeau’s principal secretary), Bill Teron (head of Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation), Paul Martin, Jr., (still associated with Power Corporation), and Maurice Strong all had private as well as public business links. In addition to Power Corporation, the companies named were Nellmart, a Martin family company, and M.N.S. Investments, which had since merged with St. Maurice Gas and been renamed Commerce Capital Corporation. Martin’s supporters said his assets were handled by others. Jack Austin said there was no conflict between his job with the prime minister and his investments in financial services. There were certainly no rules forbidding such relations, but the Liberal minority government moved fast to create conflict-of-interest guidelines, which included strictures against even the appearance of a conflict by ministers, deputy ministers, and order-in-council appointees—unless permission had been given by a direct superior. Outside directorships or active management of any commercial ventures were forbidden. Great care was urged on those who took part in non-profit activities too. Nevertheless, when the time came to actually create Petro-Canada in the fall of 1975, Jack Austin was still too politically radioactive to get the job. Maurice Strong, on the other hand, had been mainly out of the country for five years. He was a trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation. He had just been given an award by the Mellon Foundation, a philanthropy of the family that started Gulf Oil. Some also thought Strong had the ambition to lead a political party. On January 1, 1976, Strong became the first chairman and CEO of Petro-Canada. He also returned to the chair of the IDRC.

Strong launched Petro-Canada with four recruits. The president was Wilbert Hopper from the federal department of Energy Mines and Resources. (Hopper’s brother David had been a Rockefeller Foundation economist before he was made president of IDRC. By 1993 he too was on the Rockefeller Foundation board of trustees.) Strong hired John Ralston Saul, a Canadian expert on the French military/industrial complex, after he was introduced to him by a former protégé of S.G. Warburg, New York banker David Mitchell. Joel Bell, a Montreal lawyer who worked for the prime minister, was hired too. They bought oil companies from a Calgary hotel room. The first was the Canadian subsidiary of Arco. Strong was friendly with the head of Arco, Robert O. Anderson. Arco and Exxon were partners on the Alyeska oil pipeline: Arco had struck oil and gas in the Arctic back in 1968. “Bought it over breakfast,” Strong said.

Within a month of startup, Strong hired Doug Bowie, a Mormon who’d done his missionary stint in France and then worked as a political aide to Liberal cabinet ministers Gérard Pelletier and Hugh Faulkner. Bowie became vice-president/environment reporting direct to Strong, no intermediaries. Bowie’s first task was to look out for the social and environmental impacts of Petro-Canada projects in Canada’s north and abroad. He then taught other government-owned oil companies how to deal with their native peoples. Bowie found Petro-Canada was able to go places U.S.-owned private oil giants could not easily enter—such as the disputed area in the sea between Vietnam and China.

In spite of the new conflict-of-interest guidelines, Strong quickly braided layer on layer of public and private interests. He remained for a time both a trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation, chair of the IDRC, and chair of Petro-Canada. The last two were order-in-council appointments covered by the conflict guidelines. He also set up a number of new private business ventures. Strong did these deals so publicly and with such vigour that they must have been designed to feed public policy or he must have had political permission. In February 1976, a month after he started work as chairman of PetroCanada, he contacted Bill Holt, an accountant introduced to him by a former Empire Trust executive in 1971. Strong invited Holt to manage his continuing partnership with Paul Nathanson. A new entity called Stronat was registered in Alberta in April 1976. The first deal Strong asked Holt to manage was to purchase the control block in Commerce Capital Corporation, an entity that originated as M.N.S. Investments, owned by Strong, Nathanson, and Senator Paul Martin. Holt arranged a Royal Bank loan, closed the $10-million deal in ten days, and then Stronat resold the control block immediately. Stronat then joined with Ken Rotenberg of Y and R Properties in Toronto to create the Rostland Corporation. Holt and Strong sat on Rostland Corporation’s board."

These arrangements were made in the context of a surge in nationalist popularity in Quebec, similar to the situation that had first brought Strong into public life from Power Corporation. In the November 1976 election, the separatist Parti Québécois defeated the Quebec Liberal government. Looser money began to hemorrhage out of Montreal. Rostland Corporation built the new Sun Life buildings in Toronto (headquarters shifting from Quebec), bought the Arizona Biltmore Hotel, and did other developments in the U.S.

Political events in Quebec also coincided, again, with a crisis in China. Mao had become enfeebled. A struggle for power raged between the ruling faction, led by Mao’s wife Jian Qing, and a faction led by the trade-oriented Deng Xiaoping. On September 9, 1976, Mao died. For a month, Mao’s concubine held the balance of power and the keys to Mao’s treasury which held his will, his diaries, and certain other precious things. The Chinese leadership, particularly the head of security, had become avid connoisseurs.

Around the same time he organized the purchase of the control block in Commerce Capital Corporation, Bill Holt had also been asked to set up a company first called China Ventures and then SinaCorp with a Toronto marketing expert, Harvey Kalef. The China Travel Agency (owned by the Chinese government) had offered Kalef exclusive rights to distribute products made by China’s state industries. After touring China, he’d decided to purchase such goods and then resell them abroad. An accountant he knew suggested he go and see Maurice Strong, who had both access to capital and a sentimental attachment to China because an aunt of his “had walked with Chairman Mao.” Stronat put up $2 million as SinaCorp’s working capital. Kalef was to manage the project.

In November 1976, about the time of the election in Quebec and during the dangerous power vacuum in China, Kalef’s chartered Japan Airlines 747 took off from China loaded with jade, antiques, rugs, gold jewellery, and furniture and flew to Los Angeles. There Kalef had rented space to sell goods in the new Pacific Design Center. Those things he did not sell he packed on a plane and sent on to Toronto. That same month, Jian Qing was arrested, and the Gang of Four was crushed.

In January, to his surprise, Kalef was told Stronat was closing down the venture, that he was no longer needed. In Strong’s recollection, he closed the business because Stronat lost money: Kalef had bought too much and paid too much. Strong was particularly rueful about a huge supply of gold chains that no one seemed to want. Strong said he had them melted down into gold bars and sold into a rising commodity market.

I later put it to both Kalef and Strong that it appeared to me their venture had to do with someone trying to move their capital out of China in the lull before the storm. No, no, said Kalef, it had been planned months before Mao’s death. Not the case, said Strong, we dealt with state companies and not individuals.

I should have remembered that as usual with Strong, this China venture had extraordinary flexibility. There was a great deal of room for the satisfaction of many interests. For starters, cash went into China, a low value restricted currency zone, and goods moved outside where they could again be converted into a strong currency. Strong had said Stronat had lost money. That meant those running the state companies in China must have ended up with an extraordinary gain. It is interesting to note that not so long after these events Power Corporation of Montreal began to negotiate with state corporations in China: these early negotiations paved the way for important developments more than a decade later.

The New Leviathan

In 1977, while Strong was still chairman of both Petro-Canada and the IDRC, he also caused Stronat, his partnership with Paul Nathanson, to invest in agribusiness in the U.S. Dr. Carroll Wilson had introduced him to Scott Spangler (Harvard MBA), who had spent time in Africa working for the new governments of Tanzania and Uganda. Spangler then ran a Texas-based company called ProChemCo. He wanted to take over a larger public company called AZL or Arizona-Colorado Land and Cattle Company. AZL, a conglomerate, owned other companies active in feed lots, land, oil and gas, engineering. It even owned a commodities trading house and a bank. One of its ranches was the Baca Grande in Colorado.

Stronat, a private multinational octopus, purchased control of ProChemCo. through various entities it controlled in Texas, Bermuda, and the Netherlands-Antilles. The corporate name was changed to Procor. In February 1978, Procor bought an AZL convertible debenture worth $10 million. It gave AZL a two-year option to buy Procor for the same amount. Strong, Holt, and Spangler were so welcome at AZL they were invited to join its board before this deal closed and without actually owning any shares. Strong became chairman of the executive committee.

Why this extraordinary welcome to people who owned no shares? Strong explained that AZL rolled out the red carpet for him because of this little problem AZL was having with Adnan Khashoggi. Strong claimed his role was to keep Khashoggi off the board of AZL.

Khashoggi had been the biggest shareholder of AZL since 1974. One of his executives had been on the board until 1975. With Khashoggi’s help, AZL had entered a number of deals in Iraq, Egypt, and Sudan, often through the head of state of those countries. As has been detailed in a number of books, Adnan Khashoggi is another man of layered interests—an arms dealer/representative of Saudi Arabia, he has had relationships with a number of intelligence agencies. In the 1970s Khashoggi brokered vast arms purchase arrangements between Saudi Arabia and corporations of the U.S. defence establishment. At the same time, he enjoyed private business partnerships with members of the Saudi royal family who were also officials of the Saudi government. In 1975, as a byproduct of the Congressional investigations of illegal foreign and domestic campaign contributions, the Securities and Exchange Commission wondered if Khashoggi’s huge sales commissions could actually be a clever means to pay bribes by U.S. corporations to foreign officials. When the SEC tried to serve a subpoena on Khashoggi’s executives in March 1976, he left the U.S. and did not return until October 1978. It’s difficult to understand why Strong would be needed to keep Khashoggi off the board of a publicly traded U.S. company while Khashoggi was so busy avoiding an SEC subpoena.

Nevertheless, Strong insisted, there was pressure on him to let Khashoggi in the door. Strong and his future wife Hanne Marstrand first met with Khashoggi at Khashoggi’s brother’s house in London. Strong also met Khashoggi at Khashoggi’s own apartment in New York’s Olympic Towers. More often, he met with Khashoggi’s brother to inform him about AZL since Khashoggi continued to be its biggest shareholder.

In the late spring of 1978, as these matters developed, Strong left Petro-Canada. He had been asked to run for election under the standard of the federal Liberal Party in a riding just outside Toronto. (He had also been asked to run for the Progressive Conservative Party and even the New Democratic Party. Either this is testimony to his well-known flexibility of mind, or it is proof that all three parties wanted access to his connections.) Strong’s friends thought he hoped to follow Trudeau as the next Liberal prime minister.

Strong was nominated; Petro-Canada employee Doug Bowie and John Saul offered support. So did Andy Sarlos, a former Hungarian communist and official, by then an arbitrageur making money for his chief client, Max Tanenbaum of York Steel. Sarlos also worked with Sam Belzburg who would soon make a name in the U.S. as a “green-mail” entrepreneur. Sarlos liked to make money for politicians. He too thought Strong wanted to be prime minister. While waiting for the election call, Sarlos and candidate Strong tried to take over forestry giant Abitibi-Price. They failed—profitably. Strong also became a vice-president of the World Wildlife Fund International in Gland, Switzerland, a position he held until December 1981.

In February 1979, a month before the election writ was dropped, Strong suddenly resigned as a Liberal candidate. He said he had to take an active role in the business of AZL. It was whispered that he quit because Trudeau had decided to stay on as leader. While nothing important appeared to happen at AZL, very important things were certainly happening elsewhere in the world. In January 1979, the shah had fled Iran, leaving the country in the hands of Muslim fundamentalists. This disaster for Rockefeller foreign policy perhaps contributed to the untimely death of Nelson Rockefeller (which occurred a week before Strong’s resignation). Along with David Rockefeller, John J. McCloy, and Henry Kissinger, Nelson Rockefeller had been working very hard to pressure President Carter to bring the shah to the U.S.”

By the summer of 1979, as a rolling wave of panic drove the price of oil from $13 to $34 a barrel, Strong had started a new international energy company, International Energy Development Corporation S.A., or IEDC. He said it was designed to help the Third World cope with these new energy conditions by searching for oil and gas in their own territories. He based the company in politically neutral Switzerland, which required an act of the Swiss parliament since he is not a Swiss citizen. The partners in IEDC were AZL, Sulpetro, Volvo Energi, Sheikh Al Sabah, who was Kuwait’s finance minister and head of the Kuwait Petroleum Corporation; the Arab Petroleum Investment Corporation. Staff included a former Algerian politician and director of OPEC and the former worldwide vice-president of exploration for Exxon. IEDC paid licence fees to explore for oil and gas in places like Angola, Mozambique, Chad, the Sudan—and even Australia.

It was in the fall of 1979, around the time the Parti Québécois announced their plans to hold a referendum on the future of Quebec, that AZL’s business got really complex. In October, AZL began the actual purchase of Procor, the first step in a series of manoeuvres that resulted in a global version of Power Corporation. By April, AZL had bought Procor and converted its AZL debenture into common shares of AZL. Only then did Strong and Nathanson actually own AZL though they’d been directing it since 1978. In May 1980, Strong also joined the board of a publicly traded Swiss company known by the acronym Sogener. It was chaired by Léonard Hentsch, Strong’s banker friend from the Y network. Strong became Sogener’s executive committee chairman. He moved control of AZL to Sogener, and thus Sogener became the dominant but unseen partner in IEDC.

Why? What was Strong up to? Some answers lay in the nature of Sogener and its reach into various corners of the globe. Like a Swiss-French version of SNC, its engineering division’s contracts were mainly in Africa, in Angola and Libya. Sogener had just sold this engineering division to a Greek shipping magnate named Latsis, a friend of the Saudi king, Fahd. Sogener had done this transaction under the direction of Michel LeGoc, a man with his own very special political connections.’ Formerly a high French defence official, in 1960 LeGoc had left the French government and formed a mergers and acquisition company called Interfinexa with backing from important banks in Paris and Geneva.

Sogener had cash on hand when Strong joined its board. By then LeGoc had already found a takeover target for Sogener—Credit Immobilier, a publicly traded company active in real estate finance in both France and Switzerland. On Credit Immobilier’s board sat Jean Pierre Francois, said to have served with the Resistance in Lyons in World War II along with Francois Mitterrand’s lawyer, Roland Dumas. Mitterrand, who had proudly served Vichy before he served the Resistance and became a socialist, and who retained his relationship with Nazi friends even after World War II, was running for office as president of France. M. Dumas would soon become France’s minister of foreign affairs. LeGoc’s connections were such that his opinion was asked when the French government considered who deserved to get a légion d’honneur in Switzerland. Francois owned shares in Credit Immobilier and voted the shares belonging to others. After lunch with Maurice Strong, he agreed to sell the control block. LeGoc made sure Francois later got a légion d’honneur. A circular transaction ensued. Credit Immobilier bought Stronat while Stronat borrowed to buy the control block in Credit Immobilier. When this complex deal closed, Credit Immobilier paid out Stronat’s loan and raised a further seventy million Swiss francs in a public offering.

Paul Nathanson died in New York in the fall of 1980, leaving control of this huge transnational conglomerate, loaded with cash, in the hands of Maurice Strong and John Wanamaker, Strong’s friend and Nathanson’s executor. This private/public leviathan sprawled across many national boundaries and through many jurisdictions, with directors on its various boards who were also active in foreign governments. Strong and his colleagues had created the capacity for global arrangements.

This capacity was tested even as it was being formed. In February 1980 the Canadian federal election returned Pierre Trudeau and the Liberal Party to power. Right after the referendum in Quebec in May 1980, the new Liberal minister of Energy, Mines and Resources, Marc Lalonde, decided Petro-Canada should buy Petrofina Canada, a Quebec-based firm owned in Belgium. Chairman Bill Hopper talked to Petrofina Canada. He was rebuffed. In June, Strong was asked to act as an intermediary between Petro-Canada and Petrofina SA, the Belgian parent of Petrofina Canada. Strong said Hopper asked him because he knew the Petrofina directors in Belgium, “particularly Baron Leon Lambert” whose Banque Bruxelles Lambert owned Petrofina shares and like Frangois voted the shares of others. The baron, a Rothschild, was “elegantly dissolute” according to Strong, who had met him years ago at Lehman Brothers Kuhn Loeb in New York. Petro-Canada’s actions were to be kept a dark secret from Petrofina Canada’s board in Montreal, said Strong: that is why Strong asked Hentsch to make the first contact in Belgium through Sogener, whose board Strong had just joined. It was all a matter of cover.

After Hentsch made his approach to the Belgian chairman, Strong then talked to Lambert. The share price of Petrofina Canada began to soar. In November 1980, a Montreal newspaper claimed PetroCanada would soon pay $120 per share for Petrofina Canada. Denials flowed. Unfortunately, when the $1.46-billion deal was announced in February 1981, that’s what the price turned out to be. Three provincial securities commissions announced a joint insider trading investigation with the federal Department of Consumer and Corporate Affairs. There had definitely been insider trading. The chairman of Petrofina Canada and other top executives had created a stock option plan in June 1980 after Petro-Canada made its first offer. They had bought shares cheaply and sold them dearly as the market rose on rumours. The top executives at Petrofina Canada insisted they had acted without knowledge of the coming offer.